Buy Desert Travels 2021 on Amazon

ANOTHER BONUS CHAPTER!

I don’t write much about this trip in Desert Travels, so lap it up here for free.

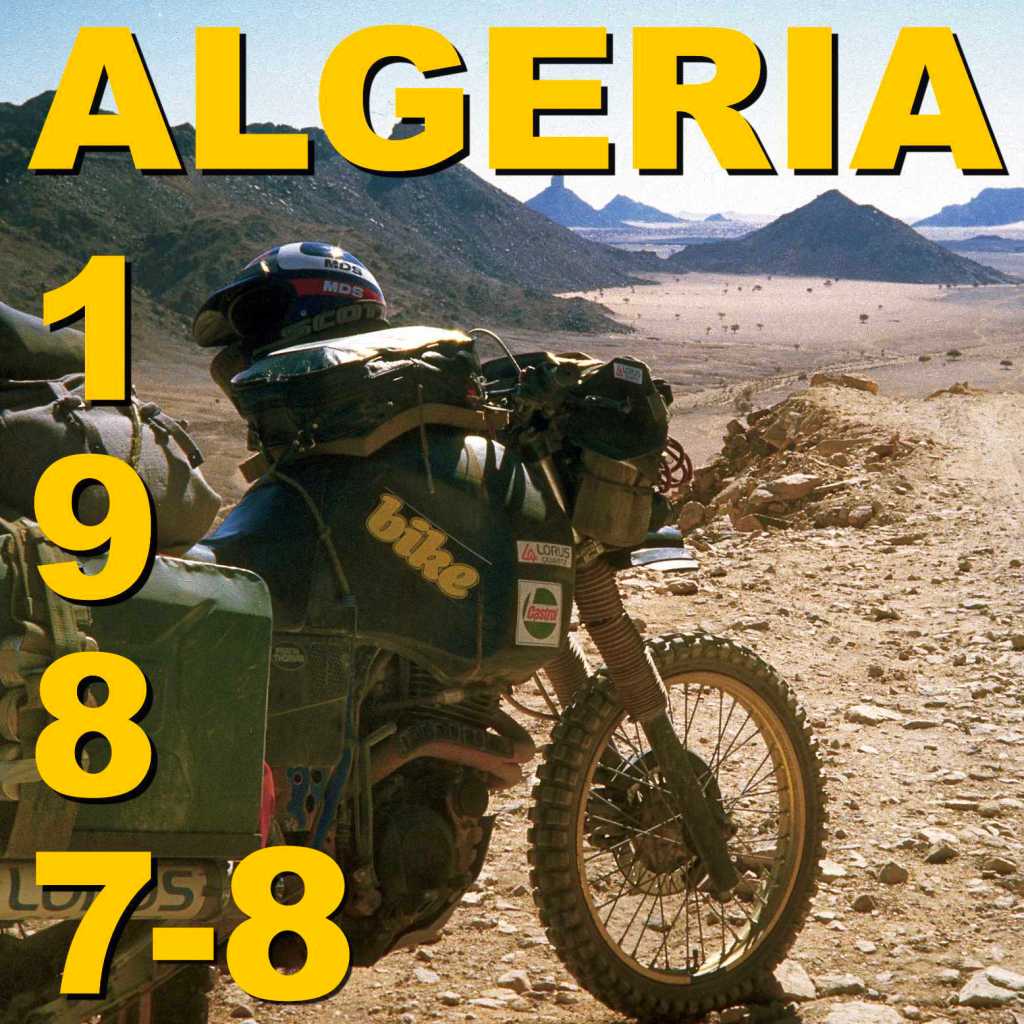

Part One ended just south of Illizi in southern Algeria where the road turned into a rough, chassis-snapping track over a desolate Fadnoun plateau, part of the Tassili N’Ajjer.

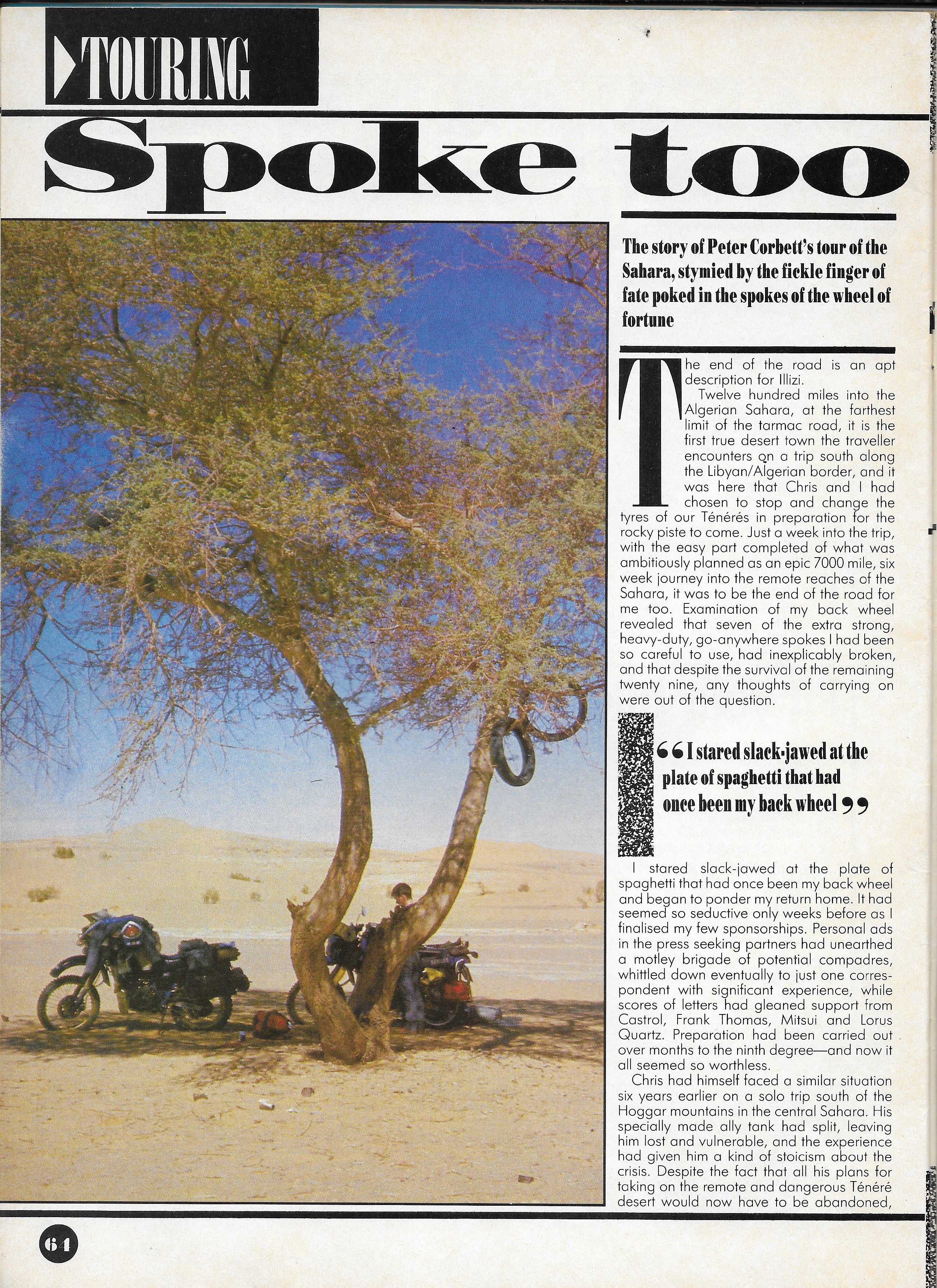

Only for Pete it was metaphorical end of the road, too. While fitting knobblies last night he’d noticed several broken spokes in his back wheel. Replacement was out of the question and carrying on over the plateau would wreck his wheel within an hour.

We chucked our old tyres up into the tree (they’d be gone in days). Pete set off for the 1300-mile ride north to Algiers, while I carried on south onto the plateau.

The next town was about 300km, with Djanet another 110km beyond that, piste all the way.

As it happens, in 2018 I passed our distinctive twin-trunked Tyre Tree alongside the now sealed road to Djanet. Acacias grow very slowly, but last hundreds of years if they don’t get chopped down for firewood.

Within a few miles the state of the track made it clear that Pete had made the right decision to turn back. You can read his story below (published in SuperBike, June 1988)

A short while later I came across these two Swiss guys coming from Djanet. They’d ridden right round the Mediterranean clockwise, also on XT600 1VJs. But I’m not sure they could have come from Libya. They were probably taking an excursion south from Tunisia before heading on for Morocco.

It had taken them days to get to this point from Djanet as their bikes were heavily loaded so they had to ride very slowly.

The system was neat and thoughtful but amount of stuff was huge, no wonder the shocks were in shock. There’s a 20-litre jerrican under the alloy boxes and I recall one had an extra large kevlar tank of 30+ litres. That’s nearly my weight alone in fuel and/or water. It must have been a hell of a rack underneath all that gear.

As I climbed further onto the plateau and it levelled off, the bare slabs turned to corrugations. To either side stretched miles of barren, unrideable sun-blackened sandstone rubble, cut by the odd sandy oued. But the track was clear so there was no chance of getting lost.

Nevertheless, suddenly riding alone and on the dirt was initially stressful. I ended the day camped in a creek bed quite worn out.

Next morning the piste turned south towards the plateau’s southern rim. At one point I got buried in the sand as the tyres were still at road pressures to protect the rims. I quickly worked out the best way out was to unload the bike, lean it over and fill in the sandy hole. The way the baggage was set up made this effortless to do, and mostly crucially: redone securely. Once the bike is upright again, it was clear of the sand and could be pushed in first out on the throttle.

Notice the three tins of sardines warming on the side of the jerrican: purpose unknown. Notice also the now sawn-off front mudguard. It seems an odd thing to have done overnight. I wonder if those two Swiss guys had warned me of the 1VJ’s overheating-prone cylinder head.

Not far from that point I upon to the epic viewpoint at the top of the Tin Taradjeli pass where the Fadnoun finally drops down to the desert floor. On the horizon eroded remnants of the plateau poke up from the sands.

Fifteen years later on Desert Riders we reached the same point on our XR650Ls after following the much rougher Tarat piste – the original colonial-era route to Djanet.

And thirty years on, in 2018 we rode back up that pass on a German tour I joined. The road now full width with Armco and a nice white line.

There’s more: I just spotted these Dakar images from the early 80s on this website.

At the bottom of the pass the famous sign: Attention, being Drunk is Dangerous.

Knowing the sands lay ahead, I dropped the tyre pressures on the Michelins. These rally racing tyres are so stiff you have to let a lot of air out to make them spread out (unless tour bike is very heavy). But when you do, the bike is transformed on soft sand..

After the village of Zaouatallaz (now called Bordj el Haouas), the truck route joined the track to Djanet and became very corrugated or thick with sandy ruts. Somewhere round here I came across a trailer stuck in the soft sand, a bit like below; same area a year later (photo: PC). I stopped to look but didn’t know how to help so just took a picture. The truck driver was annoyed.

It was easier to ride on the sands to either sides. With the Mich Deserts at 10psi or less riding off piste was a whole new game and a lot of fun. I criss-crossed the sands and low dunes, getting a feel for the XT.

After my initial nervousness on leaving Pete, I felt at home in the desert now, so decided to camp out below the escarpment rather than carrying on to Djanet.

Next morning I took this unusually good photo. I used it later for the cover of Desert Biking.

The 400-km route over the Tassili N’Ajjer plateau from Illizi to the oasis of Djanet. Even though it’s now sealed, or maybe even because of that fact, I can tell you the combination of epic views, switchbacks, sand sea finale and not least, the effort it takes just to get there, make this stretch One of the World’s Great Motorcycle Rides. There’s barely a dull mile. Tell that to Henry Cole next time you see him.

That area around Tassili N’Ajjer is probably one of my favourite places on Earth. Regarding World’s Greatest Motorcycle Rides, I really like Henry Cole’s stuff but he does seem to have an unnatural love of smooth tarmac.

LikeLiked by 1 person