See also: Desert Travels 2021

Category Archives: Project Bikes

Africa Twin – Ready for Africa

AFRICA TWIN INDEX PAGE

With AMH8 (right) sent in, I have a week and a bit to get the Africa Twin in shape for some Morocco trails and Mauritania road tripping. It doesn’t sound a lot of time but I’ve done this loads of times so know exactly what needs doing.

Or so I thought.

As I write early on in AMH: Beware and even anticipate a last-minute cock-up (‘LMCU’). While undertaking some wiring, my LBS noticed the left radiator was bent and fan jammed. I thought I’d smelt the whiff of coolant on the last couple of rides. It was clear from the damaged fairing the ex-Honda Off-Road Centre bike had fallen on the left at least once before they removed the crash bar, stitched up the fairing and sold it on. Looks like those crashes may have been heavier than they looked and my bargain AT wouldn’t be such a bargain after all. Oh well.

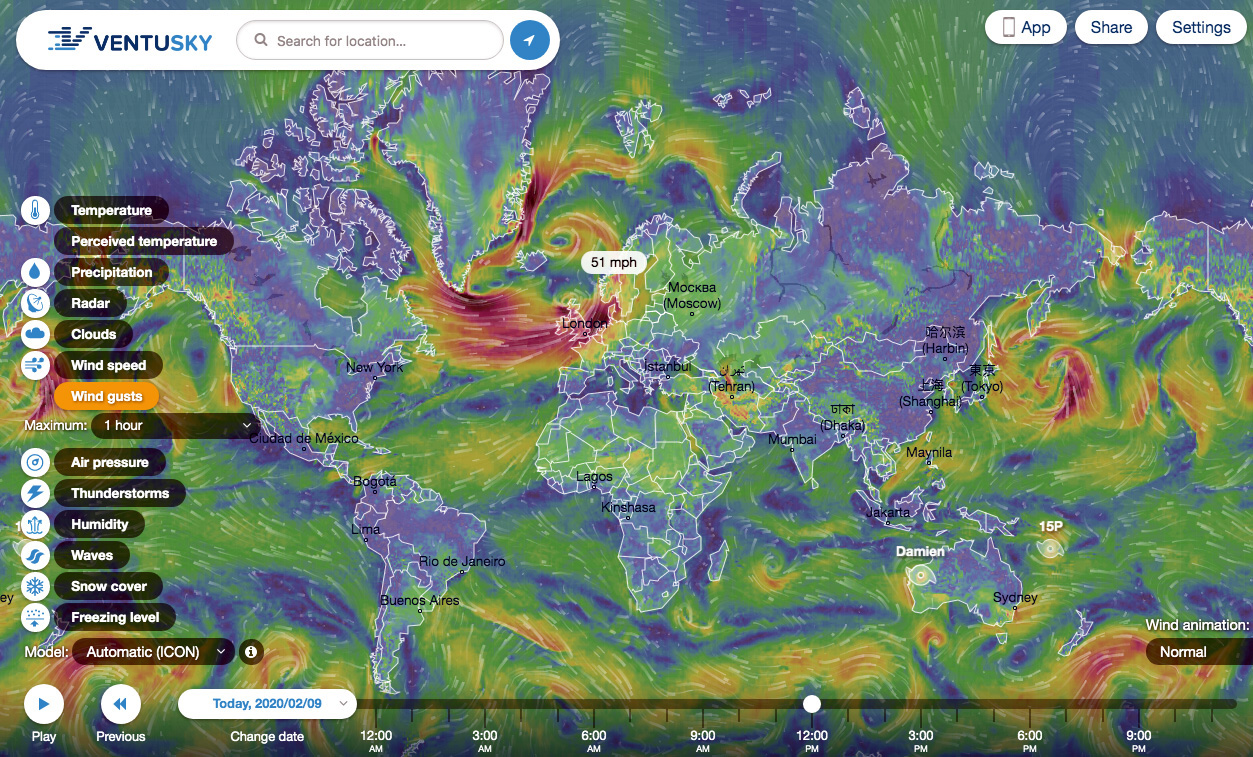

Honda parts prices? Don’t ask. Ebay to the rescue. Because there are so many ATs around I snagged a used radiator-fan assembly (left) and dropped it off at the shop. With that fixed, it now transpired the used OEM crash bar I’d bought a while back (probably also from the HO-RC) had missing brackets and my ferry was leaving next day. Luckily, the pressure was off as Storm Ciara (below) put paid to that ferry crossing and with the next one too late to get to Marrakech in time, I was left to van the bike to Malaga (£420) and pick it up after my tours. I hope that’s all the LMCUs out of the way. I really don’t want to leave our descent into Mauritania any later than it already is.

Attachments

The fixed stock screen is famously ineffective. I settled on a Palmer screen, as on the CB500X a few years ago. It consists of a taller screen mounted on a pressed steel frame with three heights and three angles (left). That should surely deliver a cruising sweet spot. All up, it adds a kilo over stock; let’s hope the mounts can handle that extra mass on rough tracks.

Riding the bike, I found with the setting as left, I could ride up to 70 with no goggles wearing a Bell Moto 3 which is as good as it gets.

While fitting the Palmer frame (start with all mounts loose and work from there) one of the lower rubber grommet mounts fell into the abyss. Universe 1; Me 0. It seems commonly done but Rugged Roads sell similar ‘top-hat’ grommets that will work and ebay is even cheaper. One thing to know: these lower screen mounts slide up into place so don’t need completely unscrewing at all. Once you’ve undone the less lose-able top mounts, just slide the lower mounts down and out.

The stock plastic ‘handguards’ are rubbish and not surprisingly, the clutch lever was bent. I was hoping my 2008 Barkbusters might get their nth outing on an AMH Project Bike, but it was not to be. The threaded ends of the Honda bars need a specific insert. Reluctantly I coughed up 90 quid for some Barks to fit an AT with, for once, no bodging required. I’ve had a good run with those old Barks and at least the scuffed black plastic covers fitted right on – the Bark bar design has not changed in all that time!

I was also hoping to re-use my Rox Risers to lessen the stoop while standing, but the Rox’s bike-mount ends are for thin bars only. You can pay crazy prices for CNC milled risers (or much less from Asia) but Adv Spec’s Risers (left) are a more normal 40 quid and come with a selection of nicely knurled shim stacks adding up to a 40-mm lift with three lengths of hex-head bolts to suit. I found about 30mm was the limit on the AT’s cables.

WTF’s the battery? It’s not under the seat. What would we do without the internet – RTFM I suppose. Turns out it’s jammed in above the gearbox (above right) but behind a ‘toolbox’ that can only be opened/removed with the 5mm key clipped under the seat (where my actual tools were located). With the empty toolbox off, I wired in a plug (above left) to run the tyre pump, but the added wiring and fusebox fouled the snug-fitting toolbox. Luckily, you can pull the box apart at the hinge (left) and just mount the front to cover the battery.

The wiring of the GPS and a USB port I left to my LBS. Here’s a good link on the fiddly job or removing the cowling, including snappy how-to vids. I don’t want to be doing what’s demonstrated below by the kerbside with tiny fittings disappearing into gutters full of rotting mid-winter leaf mush.

Though obviously very handy, there are some rambly, ill-thought-out how-do vids on ebay; some old dope droning on for 20 minutes for a <1-minute video on how to access the battery while reminiscing about his dad’s old tractor. The non-lingual vid below shows how it should be done.

Tyres

Michelin sent me some Anakee Adventures but the front looked a bit too roady compared to last year’s Anakee Wilds on the Himalayan. The AT may only be 60 kilos heavier, but has over three times the power which may chew through tyres fast.

On this trip of several thousand kilometres I’ve decided to try the ‘gnarly front – roady rear’ tyre strategy I write about. The rationale is: prioritise secure loose-terrain steering on the slower-wearing front while, on a powerful, heavy bike you need longevity from faster-wearing rears where sliding in the dirt is less problematic as you won’t be cornering this tank like a 125 MX. Anything too knobbly on the rear risks an unnerving ride, fast wear and ripped off knobs on the road.

I fitted a Motoz Tractionator Adventure (left) to replace the front Karoo which isn’t the sort of tyre I’d choose for teaching off-roading in muddy Wales on a quarter-ton AT. On dry tracks it’s less critical but the Karoo only had 5mm left (same as the rear Karoo).

The bike is front-heavy but with a centre stand and a trolley jack, once fully deflated, the Karoo just squeezed out between the twin calipers. But getting the wider, stiff and new Motoz in – no chance. I tried to undo one of the calipers but they’re torqued off the scale and the loose forks make it hard to get tension (better done with the wheel on). Instead, I loosened one fork stanchion and shoved the wheel in.

I was just about to remove the rear when I remembered I had a nearly finished DIY tubeless wheel upstairs. All it needed was taping up and a Michelin Anakee Adventure (left) slipped on with some proper tyre soap. Inflating a newly mounted tubeless can be tricky as the tyre needs to catch a seal to accumulate pressure and get pushed over the lips into place. I know from 4x4s and my old XT660Z this can be hard to do, but the uninflated Anakee ‘auto-sealed’ well enough and, with the valve core removed to speed up the airflow, eased over the rim’s lips with a pair of loud pops. A cold day a week-and-a-half later and it’s down 8-10 psi so will need watching, though I recall early pressure loss is not unusual, even on proprietary tubeless spoke sealings.

Hopefully, it may settle down but I now have a v2 Michelin TPMS to keep an eye on things and may have to get some Slime in. I’ve stuck one activating magnetic dish to the fairing at a readable angle (right) and will keep another spare in the tank bag when off-road in case the display shakes off (a common complaint according to amazon reviews).

From the state of my fairing and radiator, the OEM crash bars which came on the HO-RC bikes (and are now selling used online), don’t really do the job. But what would you expect from 250 kilos of bike hitting the ground?

I specifically want them to mount my ex-Himalayan Lomos which I hope will act as sacrificial impact-absorbing airbags. Better the bags’ soft contents get mashed than what seem to be vulnerable radiators.

The stock bash plate is at least made of metal, but it doesn’t come up around the sides of the engine which look vulnerable. On the rocky trails of the Adrar plateau I’ll have to tread carefully and have some epoxy putty at hand.

CRF1000 USD forks are leak-prone – one of mine was leaking before I even bought the bike at 1800 miles (fixed on warranty). Repairing a seal in the field sounds too tricky to do well so I’m hoping some Kriega fork seal covers (right) will keep the seals from getting worn. They’re easy to fit and remove if needed. The full-sock tubes like I had on my XCountry are better and cost the same, but require removing the forks from the bike to slip over the top.

And that’s about it. It would have been fun to ride the Honda across Spain, but this is the first time doing that crossing over many winters that the weather has caught me out.

It would have been even more useful to get the feel for the AT doing my regular tour circuits in Morocco. That too is not to be so I’ll be renting a ragged Sertao for the duration and will just have to learn to manage the AT on the fly down in Mauritania. More news and impressions on the road in March.

Africa Twin: Sealing the Rear Wheel for Tubeless

AFRICA TWIN INDEX PAGE

Tubeless Tyre Index Page

If ever a bike wanted tubeless wheels it’s the AT (and T7 for that matter). These bikes run 21-inch fronts and were initially pitched at a low price to get them moving. Choppers aside, cast wheels are unknown in 21-inch, while OE spoked tubeless wheels (as on many European 21-inch advs) are expensive. The new 2020 1100 AT Adventure Sport finally has a tubeless 18/21 set up.

MT or WM?

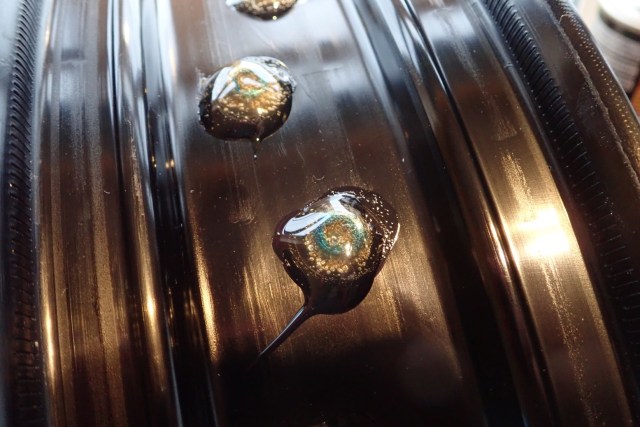

I’ve investigated various proprietary methods and, after 12 years and a lot more theoretical and second-hand knowledge, decided to give DIY sealing another go – but carefully this time and only on the back wheel (above, top) where it’s fairly easy to do. Like nearly all 21s, the AT’s front rim lacks the ‘MT’ safety lip or ridge which is important if planning to run tubeless tyres. Without it, a TL tyre seals less well on a regular WM rim (above, bottom) and may leak. And in the event of a flat, it will slip into the rim just like a tubed tyre with the usual undesirable results.

I’ve investigated various proprietary methods and, after 12 years and a lot more theoretical and second-hand knowledge, decided to give DIY sealing another go – but carefully this time and only on the back wheel (above, top) where it’s fairly easy to do. Like nearly all 21s, the AT’s front rim lacks the ‘MT’ safety lip or ridge which is important if planning to run tubeless tyres. Without it, a TL tyre seals less well on a regular WM rim (above, bottom) and may leak. And in the event of a flat, it will slip into the rim just like a tubed tyre with the usual undesirable results.

The only way around that it to get the rare, lipped, 2.15 x 21-inch Giant rim from CWC for £111. Add anodising, spokes, wheel building, their Airtight™ vulcanised sealing band (similar to DIY mastic) plus post and that’ll be nearly 400 quid. I could seal it myself and save £120, but 21-inch wells are narrow and curved and so are less suited to taping. So while CWC make my wheel, I may as well cough up for the Airtight and be done with it.

The high cost of a new wheel build is why DIY is so attractive, providing your rim is MT with the requisite safety lips. Most rear wheels, tubed or tubeless, have been like this for decades (they will be stamped ‘MT’ on the side, as opposed to ‘WM’). And the AT’s rear well is also nice and flat and 55mm wide which makes it easier to seal well.

Things you will need

- The wheel resting on a spindle

- Solvent (Brake cleaner, Toluene, MEK, Acetone, etc)

- Microfibre rag (lint-free) and Q-tips

- Runny adhesive – from Superglue to Seal-All

- Thicker sealant – like Goop or Bostik 1782

- Sealant tape such as 3M 4411N (not the 2mm thick 4412N). From £18 on ebay

- Or some etching primer and mastic sealant like Puraflex about £6 for 300mm

- A tubeless valve

Rim sealing procedure

Or…

If you’ll be in a wet environment, consider also sealing the spoke nipples from the outside.

The mastic sealant method is probably better. The tape adhesive might lift if it gets very hot; a black tyre and rim sat in the hot sun. But then, pressure building up in a hot tyre will tend to push the tape down.

Mounting and inflating the tyre

Mounting is easy as there’s no tube to worry about. Soapy beads help reduce the effort needed and tubeless tyres are actually quite flexible – or that’s how the Michelin felt. I know from cars and the Tenere years ago that home mounting tubeless tyres can be tricky. It took me most of the day to get the TKCs on to the Tenere, and that was with a pokey 2.5cfm 4×4 compressor. Because there is no inner tube pushing the tyre on to the rim, you need both edges of the loose tyre to at least make a partial seal with the rim and allow pressure to build up. When that happens, the seal improves, leakage stops and you’re on your way. Using a small car compressor and with the valve core removed to allow faster filling, nothing happened for a bit and then pressure slowly built up as input outpaced leakage. At around 35-40psi there were a couple of loud bangs as the last segment of bead slipped over the safety rim and into place.

I am fairly confident my gluing alone has made a good seal. The tape is probably redundant. Overnight there was no drastic pressure drop. If there is in the next week and I can’t fix it, I’ll swap back to the tubed wheel and will anyway take a spare tube. This time I’m not using Slime sealant, though I’m told it doesn’t affect the 3M tape’s adhesion.

I’ll be monitoring it with TPMS but a few days in it was about 8 psi down and the same again when I picked the bike up in Spain in March. So it seems to depressurised down the mid 20s psi. I seem to recall this was normal in the early days and so gave the back a shot of Slime in Spain. No more leakage.

Quick ride: Yamaha XT700 Tenere review

See also:

See also:

Yamaha’s Ténéré travel bikes

Yamaha XScrambleR 700

Yamaha XT660Z Tenere

Africa Twin

In the UK, July’s ABR show was the only chance to road-test Yamaha’s much-awaited XT700 Tenere before it reached dealers.

As a Tenere rider from the very start, and a fan of Yamaha’s proven CP2 engine from my XSR 700 (below right), I’ve been looking forward to trying the XT7. The show’s timing also allowed a fortnight before a ~3.5% pre-order discount expired, bringing the cost down to £8400.

In a line:

With the irresistible CP2 motor and legendary branding, the new XT700 Tenere will be a hit.

What they say [includes typos]

When you’re riding the new Ténéré 700, your future can be whatever you want it to be. Because this a go-anywhere motorcycle that enables you to live life without limits and experience a new feeling of total freedom.

Driven by a high-torque, 689cc, 2-cylinder engine, equipped with a special optimised transmission that gives you the ideal balance of power and control, this rally-bred long distance adventure bike is built to master a wide range of riding conditions on the dirt of asphalt.

The compact tubular chassis and slim bodywork offer maximum agility during stand up or sit down riding – and long travel suspension and spoke wheels give you the ability to get to anywhere you want. Just fill up and go! The Next Horizon is Yours.

•  Engine character and response – it’s perfect

Engine character and response – it’s perfect

• Fully adjustable, plush suspension

• Pre-load adjustment knob

• Weighs 205kg (unverified). Same as my 660Z and less than my CB500X RR

• Flat but grippy textured seat

• Brakes feel good, road or dirt

• Brisk and agile on the road

• A display scroll button now on right bar

• 25,000-mile valve-clearance intervals

• Well set up cockpit

• Centre stand – at least an available option

• OMG – no beak!

![]() • Is it such a bargain? Over £2k more than an MT-07

• Is it such a bargain? Over £2k more than an MT-07

• At 16-litres, the tank could use a couple more

• Top-heavy at a standstill

• At 34.5″ (875mm), the stock seat is high (there are lowering options).

• Non-adjustable screen

• Handguards are all plastic

• Screw-in filler cap

• Tall riders will need bar risers to stand comfortably

Modern bikes from established manufacturers are now predictably brilliant, and recent launch reviews raved about the XT700. No great surprise there; Yamaha took their time getting the new Tenere just right while keeping the price down. We’ve all read or experienced what happens when that doesn’t happen. And like Honda’s Africa Twin of a few years ago, Yamaha chose to dodge a ‘because-we-can’ horsepower and tech-war with the KTM790 Adventure with which the XT7 is being inevitably compared.

The new Tenere shares the same CP2 motor with the MT-07, Tracer tourer and XSR retro. Everything else is new or different. Since being introduced in 2014, all three have combined to make one of the most successful model ranges for Yamaha. By now over 100,000 units have been sold worldwide and the XT700 will add to that figure just a fast as they can bang them out.

They may have saved time by ignoring electronic aids but, crucially, Yamaha didn’t cut corners on the suspension, which often defines budget Jap bikes these days. And the XT includes one of my favourite gadgets: a 26-click hydraulic pre-load adjustment knob (PLA; left) on the piggyback shock. It means you don’t have to faff about with C-spanners, or more often, hammers and chisels, to alter preload. It may be right under the mudguard collecting crap off the tyre rather than to one side, but this sort of real-world prioritising speaks to riders like me whose eyesight is now too poor to be dazzled by colourful TFT screens, quick-shifters, cornering ABS, traction- and cruise control plus ESA and over a dozen engine modes. Years of hard-won experience have taught us to simply ride appropriately for the conditions and location, be that negotiating a rainy winter’s rush hour, or off-roading alone in the middle of nowhere (left).

Hook up a throttle cable to a CP2 motor and that’s all the traction control you need.

Indeed – just like the old Tenere singles, many commenters (and they are legion) are citing the XT700’s very simplicity including lack of riding aids, as integral to its appeal. It’s kept costs down, doesn’t radically affect the bike’s day-to-day usability, and is one less thing to light up the dash should the electronics play up.

That leaves ABS, which is now mandatory on all new bikes in the EU. Unlike the list above, it’s a safety feature I welcome, and at a standstill, can be disabled for the dirt. (On loose surfaces ABS can cut in too soon and extend braking distances. You don’t want that, though I’ve found at normal dirt speeds ABS on bikes is rarely a problem.)

My impressions

Compared to the original T7 concept from a bike show back in 2016 (left), the production bike looks as good, but not dazzling. According to a tape measure, it has nearly the same dimensions as an Africa Twin (right); in fact it’s two-inches longer but it sure looks less bulky. (There were loads of ATs at this show. Great to see how popular they’ve become alongside the You Know Whats).

With a 32-inch inseam and workboots, on the standard 875mm-high (34.5″) seat I was able to get my feet flat on the ground, but with little knee-bend to spare. There’s a lowering kit (£228) which includes a link and, combined with a 20-mm fork drop, lowers the seat height substantially to 837mm (32.9″). Plus there’s a higher, rally seat. I noted coming back to the Yamaha stand one normal-sized bloke struggling to manoeuvre his T7 into place; one foot in the air, the other on tiptoe.

I’d definitely consider the lowering kit, even if the seat will probably lose padding and lowering links (‘dogbones’) alter factory-designed suspension geometry. At least the Tenere’s suspension can be easily retuned, should you notice a difference. I also see on this YT video there’s also a two-part seat option (right), and the rear section can be swapped for a rack.

Although the CP2 motor is a slim unit, they’ve maintained that overall impression with a narrow seat and screen. Even the LCD display is in portrait format to suggest lack of width. This is not a wide-arsed GS12 or XT1200Z, and because of that feels less intimidating and more fun to ride on and off road.

The plain LCD digital dash is a rectangular version of the round unit off my XSR: switchable Imperial/metric speed, gear, fuel and time readouts, plus the same range of seven other metrics in various formats, but with only room to display one at a time. On the MT-07/XSR you reached over and scrolled with a button on the dash. The XT700 has a Select button on the right bar (below) which does the same and so makes it much easier to change the display on the move. Cycling the button seven times hits them all. Neat and simple.

• Ambient temperature (C or F)

• Engine temp

• Average mpg (or other formats)

• Current mpg (ditto)

• Odometer

• Trip

• Another trip?

Up here you also have a power outlet plus a place for another one, and a bar above the display for mounting a navigation aid or even a roadbook at near eye level.

The CP2 (left) may be narrow, but it’s a tall wet sump motor which makes it less suited to trail bikes in need of ground clearance without getting too top-heavy; there’s a lot of mass above those piston crowns and a fuel tank too. This is partly why four-stroke trail and dirt bikes are traditionally dry sump, with a pump and an oil reservoir fitted somewhere.

While repairing my XSR I remember wondering if I could have realistically reduced the 3-inch depth of the protruding sump, even though it was fairly well surrounded by the silencer box and header pipes. Some oil volume would have been lost.

On the XT7, under the skimpy 2mm alloy bashplate, it’s the same deep sump, so the longer suspension makes the whole bike top-heavy at parking speeds. It’s nothing new with such bikes, but I did have an … oh shit! moment, lowering the bike onto the stand on an off-camber path to remove dry grass from the hot pipes. It’s a long old way to fall, even at zero mph.

The narrow but steeply raked screen looked like it should do the job. Housed in the rally-style fairing, you’d also hope that, with four-LEDs plus two smaller day-lights, the headlight set-up (left) will do more than just look good once the sun goes down. Sat on the bike, I liked the high, wide but slim feel and, apart from the saddle height and weight, felt right at home on the XT7.

For a bike carrying the Tenere name of the legendary ‘desert within a desert’, only the modest fuel tank capacity spoils the picture. You imagine a sub-205-kg wet weight by any means possible was locked into the design brief, and the easiest way to play with that is tank volume. It’s only 2 litres bigger than my XSR, but if the XT700 averages the same consumption, that will still add up to a range of 420 km (260 miles), or between 330 and 510 km. Right on target for a travel bike.

One easy way of unobtrusively supplementing fuel range on the XT would be to attach flat fuel containers low down to the accessory engine crash bars (right; another 200 quid). Fyi, the bike I rode had recorded an average of 58mpg / 20.5kpl since the tank had been refilled. Not spectacular.

T7 test ride

The 45-minute test ride – part of the Tenere Tour doing Europe at the moment – was an escorted run. This meant little chance to grab good photos. About eight German-registered XT7s were available, all with a few light scrapes from previous test rides. My bike showed 3800 miles on the clock.

You had to book a time allocation. I arrived before the show gates opened and even then, got on the second or third slot that day. I overheard that by the end of Friday the whole weekend had been booked out.

Initially, the route followed a marked grassy trail around the spacious grounds of Ragley Hall, before taking off on a blast around Warwickshire’s lush, midsummer backroads. I was told all these pre-production bikes were all destined for the crusher (a common practice). No chance of getting an ex-test bike cheap. Sad face.

On the trail

Pulling away, who can resist the instantaneous grunt of that CP2 engine, characterised by its 270-° crank timing, (left; more here). In the modern era 270 was first used on Yamaha’s TDM900 but has now become almost ubiquitous on big parallel twins. It’s one of my all-time favourite motors, harking back to my XS650 or of course, your favourite 90-° V-twin, whose firing pulse is replicated by a 270-° P-twin crank, but in a much more compact engine. Thanks to revised injection mapping and a new pipe and air box, the XT7’s added low-down torque was noticeable right away and might even have been described as snatchy. The radiator is a little different, too.

According to Yamaha specs, the XT700’s 72hp at 9000 rpm is 5% less than the three CP2-engined road bikes, but it has the same 68Nm of torque at 6500rpm. I imagine the XT’s long, rally-style pipe (left) helps deliver that low-down torque, compared to the stumpy XSR/MT-07 silencers (inset).

The way my clutch was adjusted, initially, the unfamiliar bike was a bit of a handful in the slower sections – or maybe it was just a little snatchy at low rpm. This wasn’t helped by the tall first gear and shallow-blocked Pirelli Scorpion Rally do-it-all tyres on the flattened dry grass with all the grip of old lino.

Tubeless spoked rims (as found on the XT1200Z) would have blown the XT700 budget, but I have a hope that the rear rim has safety beads, which make sealing with Airtight or BARTubeless a possibility. On the front that’s less likely, but safety-beaded 21s are available. As it is, a tubeless rear is more useful, as on the road that’s where most flats occur.

Gearing

Riding along in first hand off the throttle at the 1400rpm tickover, the bike fuelled cleanly but the speedo registered 7mph. As with so many bikes in this category, that’s normal but too fast for trickling uphill round gnarly hairpins without slipping the clutch, though I recall the XSR managing that surprisingly well in Morocco. Problems may occur doing that for too long in hot conditions, but let’s be realistic: this is a 200-kilo bike. Despite the exuberant promo images (left), the elephant in the adventure-motorcycling room is the belief that bikes two or three times the weight of their pilots are manageable on anything more than smooth gravel tracks. For most, they make fun road bikes with a cool, adventuresome image.

Compared to the MT-07 (and probably XSR), I read here that they’ve added three teeth on the rear sprocket but taken one off the front, ending up with 15/46. That adds up to an identical 0.33 final-drive ratio unless I am very much mistaken, so it may have more to do with chain/swingarm clearance for the longer-travel suspension. It’s actually the taller 18-inch wheel with a 150/70-R18 tyre which increases the overall diameter to raise the gearing. Unless they’ve taken the trouble to modify the internal gear ratios, any mention of ‘… special optimised transmission…’ (as above) is presumably just marketing flannel.

Sat upright, grappling the wide ‘bars, at least the big trail bike’s commanding seating position makes you feel both in control and nimble; ready to respond with confidence to whatever’s ahead. It’s not a new idea, but squidgy rubber inserts in the footrests (right) also mean you get the benefits of comfort and isolation sitting down, with boot soles compressing the rubber and biting the serrated metal edges when standing up.

Doing this, as expected, I found the fatbars an inch or two too low to stand comfortably (me: 6 foot 1). That can be fixed with Yamaha risers or similar, but I did notice that to get the stock bars up, the rubber-mounted bar mounts (left) are even higher than they were on my XSR. Add some risers and that’s getting on for six inches of leverage on the triple clamp mounts when hammering over rough terrain or when the bike falls over (my XSR ones were bent in the write-off crash).

This may be a red herring and only relevant to taller riders who expect to need to stand, but it’s a problem I’ve encountered on projects when trying to convert what’s essentially a road bike into an all-road travel bike – particularly when attempting to Tenerise a TDM (right) a few years back. You can’t just fit some apehangers and hope for the best. At the front, the XT700 is still a low-headstock, MT-07/XSR road chassis (more below).

Who knows what the settings were, but the suspension coped fine on the trail at our modest speeds. It soaked up what few bumps I could find and had it not, there’s preload as well as rebound and compression damping to meddle with. It was hard to make a worthwhile evaluation in our 10 to 15 minutes on the grassy trails, but it’s unlikely the Tenere’s suspension will urgently need the same Rally-Raid treatment which their CB500Xs benefit from. A great motor and good, adjustable suspension is half the battle won.

The brakes too had enough feel plus ABS back-up to inspire confidence and stop you embarrassing yourself. I never knowingly actuated the ABS.

It might be an off-road clearance issue, but I‘d have prefered a powerful single rotor on the front; it saves weight and worked fine on an NC750X I tried later. The XT660Z single (right) which this bike effectively replaces was unnecessarily lumbered with twin front discs. The front wheel on that thing weighed a ton.

On the road

Truly, there’s nothing more I need from a motorbike engine apart from 100mpg: smooth, ambrosia-like power delivery right off the throttle, but with that sweet, characterful lumpiness of warm rice pudding and which can never be called harshness or vibration. Just as it was on my XSR. I bet the manual Africa Twin and some Triumph twins are similar – a KTM790 I rode wasn’t, and it’s what’s missing from Honda’s bland CB500X.

Once on the highway, the escort riders didn’t dawdle unnecessarily and the XT700 took it all in its stride. Potholes and drain covers didn’t faze the springing, the brakes handled sudden bunch-ups well, and the moto just pulled through it all as fast as you wanted to go. I could have kept going all day.

You’re sitting on 200mm or 8 inches of fully adjustable and compliant suspension with USD forks and the PLA on the back. As it’s so easy, I cranked the knob all the way in to 26: the ride was much firmer – ready for some heavy throwovers and a dusty trail. Back at the normal mid-setting, the feel is of being able to hit irregularities with less wincing while – if you know what you’re doing – tuning the damping in both directions as well as easily setting the sag; the vital metric which is more or less 30% of total travel).

Where 60 to 70mph was possible, the blast from the slim screen hit me at nose level but still gave useful protection. I could crouch and get out of the wind, but wearing a Moto III didn’t help the aerodynamics. You’re riding a motorbike; don’t expect a turbulence-free cocoon. Just as since time immemorial, the mirrors shared the rear view with my arms but were blur-free.

After a while I noticed that the plastic clutch plate and arm cover (right; not present on earlier CP2 bikes) pressed into my right shin – and this was without knee-high boots. Maybe I have fat calves but it was never an issue on the XSR7 and at least two other reviews have mentioned it. I’m not sure what it does – stop boot rubbing? It could be easily removed.

The stock bashplate (left) is skimpy, but it’s a start. For 200 quid Yamaha do an optional version (right) which better covers the vulnerable water-pump and inlet pipes. These components were good and mashed following a low-side on the written-off XSR I bought. The engine bars pictured far below will work with the standard bashplate.

Revised chassis

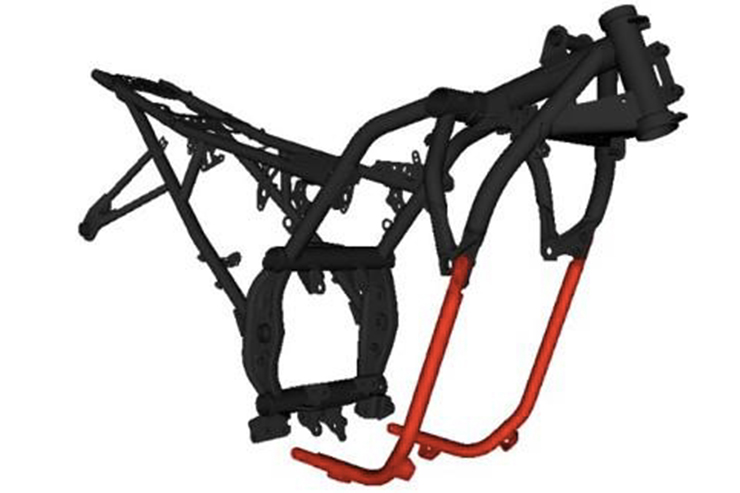

The potential of lively owners grabbing big air required a heavily revised frame on the T7.Among other things, on the XSR700 etc, the top of the laid-over shock attaches to a lug on the top of the gearbox casing (above right); an expensive repair if that sheers off during a Great Escape (left). The XT700 has a different linkage for a vertically positioned shock which mounts to a chassis cross-member which is better able to contain shock loads.

They call it double cradle, but you can clearly see above left, it’s not a closed loop. The new (red) downtubes meet the footrest mounts because, using the same rationale as the shock, a bashplate is better mounted to a chassis than a crankcase.

I didn’t get a chance to remove the seat and panels to eye up the rear subframe, but again, from the image top left you can see the triangulation is much greater, partly because the silencer needs to hang off it. Round the headstock they’ve added additional bracing.

Is that an alloy sidestand? If so I presume it’s solid cast and will be up to supporting the weight of the lent-over loaded bike when oiling the chain or removing the wheel. They do offer an optional centre stand which, having had one for the first time in years on the Himalayan, is a worthwhile redundancy on a travel bike.

The first batch of XT700s are being assembled in France right now from parts made in Japan. This must mean the MBK Industrie plant in Saint Quentin, south of Lille. A few early-adopters got their pre-orders in July 2019; the rest got them from September onwards when production resumed after the August factory break.

North America gets bikes shipped directly from Japan some time in late 2020 (as will Australiasia and maybe RSA, following late-2019 deliveries from Europe). The official explanation claims it’s: “Due to differing government regulatory standards and factory production line schedules.”

Either way, the wait of a year ought to help eliminate any teething problems, unlikely though they are with the established CP2 engine, at least. And a Japanese-built XT700 might be something to boast about. After all, from 2020 KTM’s similar 790 is said to switch assembly to… O M G.. China!

Summing Up

The XT700 is a hard bike to dislike. It lacks the weight of the 850GS and the added bulk of an Africa Twin, the harshness, racket, blingy complexity and cost of the KTM790R, and the relative blandness and cheap suspension of the CB500X as well as, dare I add, an NC750X. Like the CB-X, it’s a modern-day UJAM, not extreme in any way, be it suspension travel, power delivery, appearance, electronic sophistication or price.

You see reviewers mention ‘only 72hp’ for a 689-cc-engine and you really have to chuckle. It actually makes nearly 15% more power per litre than the 790, if that matters at all, but either way it’ll do 120, cruise comfortably at 80mph, and overtake swiftly uphill and into the wind when needed. How often do you ride much faster, while still being able to hit the trails with confidence?

I came to this test ride fully expecting to love the new Tenere – a bike I tried to emulate two years ago with my XSR Scrambler which, along with the Himalayan, was one of the most enjoyable rides I’ve had in years.

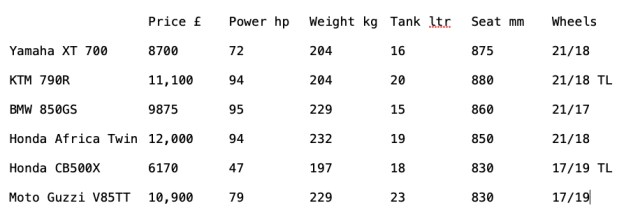

I was even considering buying a T7 after the test, with all the risks of delayed delivery, teething problems and depreciation. For the price and the weight, nothing else new in the table below comes close once you factor in its genuine off-road ability for its class. But I’ve not bought a new bike in the UK for nearly 40 years; to me it’s just too extravagant with so much good nearly as good used stuff out there. In a way, knowing that it all turned out well for the XT700 is good enough for me. For the sort of riding I still aspire to, I’d be more comfortable with something a bit lower and lighter.

If not an XT700 then…

The man from Honda hinted an 1100 was in the AT pipeline, but right now CRF1000L Africa Twins with about 10,000 miles are going for under £7k. I know, I bought one later. That’s a similarly grunty 270-degree twin (with a DCT option), but in a bigger bike with a lot more weight. BMWs hold their value annoyingly well; used year-old 850GSs with KTM-like tech, tubeless wheels but an AT’s weight currently start at £9k. Meanwhile, there are Rally Raid CB500Xs going from £4300, plain, old-model high-milers from under three grand and 2019 CB-Xs with the desirable 19-inch fronts from just £5200.

The XT700’s profile and price is pitched midway between the ultra-accessible CB500X and ageing V-Strom, the bulkier Africa Twin and the 790 Adventures and BMs. Even if dynamically you’d assume the 790s must be better out of the crate for hard off-roading (I did try one; not for me), realistically any 200+kg bike can only be exploited by a skilled and fit rider. With talk of a bigger AT, people are wondering if a 7-850cc Africa Twin might spin off from that. Until (or if) that ever happens, the XT700 will have a well-deserved market niche all to itself.

Himalayan 410: 4000-mile review

Himalayan 410 Index Page

2025 Himalayan 450 3000km review

Updated January 2024

In a line:

Didn’t miss a beat over a month; no one was more surprised than me.

• At £4000, with the stock equipment it [was] a bargain. (Now £5050).

• At £4000, with the stock equipment it [was] a bargain. (Now £5050).

• Low, 800mm seat – at last a travel bike not limited to tall people

• Enfield build quality stood up to it

• Efi motor pulled smoothly up to 3000m (nearly 10,000′)

• Michelin Anakee Wilds (run tubeless) – great do-it-all tyres

• Low CoG and 21-″ front make it agile on the dirt

• Rear YSS shock showed up the harsh forks

• Yes it’s 190kg, but road and trail, it carries it well (or low)

• Subframe easily sturdy enough for RTW load carrying

• Economy went up and up: averaged 78 mpg (65 US; 27.6kpl; 3.62L/100k)

• 400km range from the 15-litre tank – about 250 miles

• Valves need checking every 3000 miles – not practical

• Valves need checking every 3000 miles – not practical

• Weak front brake on the road (sintered pads are a fix)

• As a result, front ABS is a bit docile

• Stock seat foam way too soft for my bulk

• Tubliss core failed on the front; replaced with inner tube

• Centre stand hangs low – but can be raised

• Small digit dash data hard to read at a glance

• Compass always out – a gimmick

• Head bearings notchy at 4000 miles, despite regressing @ 1200 (replaced on warranty @ 5000)

Review

Following a test ride, I bought a used Himalayan with just under 1000 miles. And following the make-over detailed here (summarised in the image below) I picked it up in southern Spain with 1300 miles on the clock. So, like many of my crudely adapted project bikes, I’d barely ridden the thing or tested the modifications. With a Royal Enfield this did feel a bit more of a gamble than usual and, on collection near Malaga I was all prepared for the worst.

Far from it. The Him started on the button, ticked-over like a diesel, and after the ferry crossing and fighting the usual headwind gale down the Atlantic motorway, I arrived at a cushy hilltop lodge near Asilah feeling moderately hopeful, while still braced for a kick in the nuts somewhere down the road.

Riding an untried, near-new machine, saddled with Enfield’s possibly outdated reputation for reliability led to stressful days, waiting for something to play up, either with the bike or with my mods. I had the same feeling with BMW’s XCountry years ago. But riding my first piste: the lovely Assif Melloul gorge route out of Anergui inspired confidence. The low-slung weight and chuggy motor made this a great trail bike!

Engine and transmission

Much is made of the 410LS’s meagre 24hp (or even 22) because we’re so used to bikes delivering over 100hp per litre. Don’t forget Honda’s ill-concieved CRF450L makes about the same. It’s when you combine 24hp with the strapping 190-kilo wet weight you’d think it can’t possibly work. Yet it does – and in a way that you won’t find on a similar powered and much lighter 250 trail bike like the WR250R, KLX250S, CRF250L or 300L which I’ve also used, as well as a 310GS. I prefered riding my REH to all of them.

It must be down to the way the long-stroke, low compression, two-valve motor delivers it’s modest power, like something from the apogee of Brit biking half a century ago, but without a millstone for a flywheel, it revs more freely. The Himalayan may have the power of a CRF250L, but it has the torque of an XR400: 32Nm at 4250rpm (1150 lower than the XR). Combined with counter balancer and unexpected refinement, despite wide gearing it’s a very satisfying bike to ride. It won’t hurl you from bend to bend, it just chugs along steadily but without the sensation that you’re missing out or grossly under powered. The key is to maintain smooth momentum which is very much the riding style I aspire to. It’s an easy bike to enjoy on the empty roads and even emptier trails of southern Morocco. Duelling with congested traffic or tackling busy alpine passes may not be such fun.

Until the end of my trip – by which time the valves were technically well overdue for adjustment – it started on the button without the ‘choke’, ticked over once warmed up (probably needs adjustment too) and fuelled cleanly up to 5000rpm and nearly 10,000 feet (3000m).

A lot of it must be down to accepting the Himalayan for what it is, but there was never a moment on my ride when I thought ‘FFS! I wish this thing had more poke’. I tried some super grade fuel in Morocco but didn’t notice the difference that some claim (I know in the US fuel octane varies widely). However, once back on Spanish fuel, it did seem faster and smoother, or maybe I was just rushing for the finish line.

One thing the Trail Tech temperature sensor did highlight was how hot the air-cooled engine runs – up to 240°C at higher revs with a load on. Note I say ‘hot’, not over-heating. On my bike it’s reading from the spark plug, about as hot as it gets in there. Running down hill it might drop to 160°C or so. Either way, especially with an air-cooled motor, it’s good to know how hard the engine is working and when it may be time to back off.

Oil consumption was zero up to a pre-emptive oil change at 3000 miles. Straight 50W Moroccan was all they had (a bit thicker; better for hot weather) and I had the feeling consumption increased briefly after that, maybe 200ml in 2000 miles, but then it stopped.

The gearbox is a lot less clunky than some. Originally, I thought first gear would be too tall off road (a common complaint I have) but, helped by the low-down torque, it’s well matched to the Himalayan’s modest trail biking abilities which are governed mainly by its weight. One time in deep soft sand, the gearing was too tall to move the bike forward – the chain jumped on the front sprocket instead (see below).

The chain had a hard time in Morocco: conditions too gritty to lube most of the time. On longer road stretches I hand-lubed with a toothbrush from small bottle of Tutoro oil. As a result I adjusted it three times in 4000 miles – more than normal, even for a stock chain. Again, you have to assume the stock chain was chosen for its price, not quality, but with a bit more care and lube it should last 8000 miles.

Suspension

Normally the suspension is where a budget bike shows its limits once pushed on rough roads and trails, with heavy loads. Plus I tend to leave my tyres at road pressures unless absolutely necessary, so as a result off-road the my suspension can feel harsher than it could be.

On the rear there’s only preload adjustment and nothing on the front, but the Himalayan surprised me with firm suspension. Before I realised this, I’d fitted some inexpensive fork preload caps, (set at zero), and a YSS shock that had 1cm of length adjustment and 35 clicks of rebound damping. I had the YSS fitted on the settings out of the box (more here) which worked fine once loaded up and on the dirt. At one point in Morocco I screwed the rebound in 4 clicks (more rebound?) but can’t say I noticed any difference.

Overall, I suspect the stock shock (inset above) would have been OK, but you have to assume the YSS is an improvement because there’s more adjustment and it’s red. It certainly felt better than a twice-as-expensive Wilbers on the XSR last year. Over the trip it loosened up a bit and bottomed out maybe once.

If anything the front forks are now shown up by the YSS. YSS do offer a fork kit but in the UK it’s £330 (though it seems you can buy springs plus the emulators for half that). Bottom line: no great need to meddle with the stock suspension for normal riding.

Economy

It seems that even at 1300 miles the air-cooled REH was still running in. As I added the miles the economy improved, eventually averaging 78.7mpg (27.8kpl; 65US). With the 15-litre tank that’s an ideal range of just over 400km. Riding with some 310GSs for a week, my mpg was near identical to the more powerful and lighter BMWs. The gauge on the tank is pessimistic and the warning light plus a trip reset comes on with a good 100km left. Hot, cold, high, low, the fueling itself was glitch-free. Fuel consumption data here.

Comfort

Thanks to a counter-balanced and non-ginormous capacity, the REH is very smooth for a single. I did feel some tingling in my right hand after hours at the bars which could have been from over-gripping a heavy throttle. I’d have used my throttle handrest had I remembered it.

One of the best things about the Himalayan is the low seat of 800mm or 31.5 inches. At 6′ 1″, it’s actually a bit too low for me, especially once my mass sinks down through the soft foam, but at last there’s a travel bike which isn’t limited to tall people, while still having useful ground clearance. It never scraped out on the dirt

I needed more height with firmer foam, inexpensively achieved with a couple of 20mm neoprene slabs under a Cool Cover. It enabled 500-km days with few stops, but on rough tracks still gave soreness, probably because I wasn’t standing up or letting the tyres down enough. I also thought the seat could do with levelling out to stop me sliding forward on the slippery, aerated Cool Cover.

My seat bodge was not a night-and-day transformation, but by the end of my trip it didn’t cause any discomfort over long days on the road. I’m less convinced now that I need to improve it some more.

The 50mm bar risers managed to not snag the screen on full lock and nearly reduced my stooping when standing up – another inch would have done it. I might have cured that stoop by removing the footrest rubbers, but to be honest I liked the comfort when standing (in ordinary slip-on Blunnies). Otherwise, for wet conditions, consider fitting wider footrests if you’re off-roading. I hear DR650 pegs nearly fit.

Some say it will clock 80 but I set myself a self-imposed cruising limit of around 65mph (where possible). At this speed the screen did a pretty good job, even with my wind-catching Bell Moto III helmet. Others claim the mirrors create turbulence and are better moved or changed. I suppose this is possible but that complaint is a new one on me. Let’s face it: it’s a motorbike out in the wind, not a space capsule. Some turbulence will be evident.

On the dirt

The Him took to the dirt so naturally, I didn’t even notice it at first. The key attributes must be the Michelin tyres, low seat and firm suspension. The 21-inch front wheel must help too, as does the torquey motor, getting round the wide gearing. And the otherwise ordinary brakes are just right on the dirt.

The Him is a plodder, but then so am I. You won’t be pulling wheelies, launching off jumps or bouncing off berms. For that the bike is just too heavy and low-powered. It’s a travel bike, not a dirt bike and in all the miles I never ever had a sketchy moment on the dirt, nor wished the bike was something else.

I reached the Himalayan’s limit in the sandy gorge on Route MW6/7 in Western Sahara – same place I’d struggled with the WR two years earlier. This time I traced a better route along the valley but the flooded waterhole was now a dry mass of deep sandy ruts in which the Himalayan would bog down for sure. I aired down, pushed around the side in first gear, but stopped once the chain jumped on the front sprocket from the strain: the torque had got the better of the weight, tall gearing and deep sand. The Himalayan doesn’t have the agility or power to handle deep soft sand – for that you want an unloaded KTM 450.

Durability and problems

It’s a short list. Apart from what’s below, nothing broke or even came loose, but I’ve not seen the bike since I left it at Malaga. A closer inspection may reveal more.

Stock bike

• Head bearings got notchy by 4000 miles, despite regreasing

• Chain needed adjustment every 1000 miles

• Exhaust guards dented

My mods

• Tubliss core leaked around valve stem, then packed up

• Michelin TPMS packed up – twice

Summary

The Himalayan is a unique all-road travel bike, one that not only looks fit for the job as many adv bikes do – but that’s actually equipped for it and performs well, too. You might not think 24hp and 190 kilos (420 lbs) adds up, and for some it won’t. But for your £4000 or $4500 you get a lot of kit that’s no found on similar bikes. Don’t dismiss it as a shoddily assembled Asian cheapie, or anything to do with the Bullets. The bike has caught on, and in western markets the demand for the BS4 has outstripped importers’ expectations. If you’re curious like I was, try one. You might also be surprised.