Are we ready for electric motos? Probably not, but I did a twitterpoll and it looks like we certainly want them.

2025: UBCO goes bust

I’ve always liked utility bikes (‘ag bikes’, ‘farm bikes’) where functionality is measured in terms of load carrying and off-road agility, rather than tarmac-creasing acceleration or foot-long suspension travel. They even get their own section in AMH8, left. For the right sort of gnarly adventure, or with a recalibrated attitude towards pace, bikes like Honda’s AG190 (left) could make a tough little travel bike.

Ag bikes possess that do-anything, go-anywhere appeal, which must also be behind the adventure motorcycling phenomenon. Yamaha’s TW-inspired Ryoku concept of a few years ago (below right) seemed to bridge both segments.

Whether intended or not, UBCO’s 2×2 electric utility ‘moped’ may also benefit from this ‘I-could-if-I-wanted-to’ conceit. People need personal mobility, sure, but many like to be feel cool while doing so, be it in a RAV 4 or on a GS12 or Raleigh Chopper.

While staying in an affluent suburb of Sydney recently, along with skimpy urban scoots like the Sachs (above left), Chinese urban retros similar to the Mash Roadster as well as a few XSR7s outnumbered anything else I saw on two wheels there. In fact it’s said bikes like these are now beginning to outsell adventure-styled bikes. Expect Bike Shed franchises to start popping up like Pizza Huts.

The Ryoku never got off the drawing board, but Honda’s recent X-ADV adventure scooter sought to capitalise on that urban adventure cachet. But after riding one – and even though I now have DCT out of my system – I felt something more akin to the current Ruckus moped (left; not sold in the UK) would have been more fun.

In Australasia and South Africa, ag bikes have been on the scene for ever, but have changed little since the 1980s. What you want is an ag bike’s utility with scooter-like ease of getting on and off – a mini X-ADV. But do you also need 2WD and would you choose electric?

2WD motorcycles

You can be sure that one long winter some obscure engineer-farmer has experimented with front-wheel drive long before most of us were born. The vid below is one of many crazy-arsed compilations on youtube. And a couple of years ago Visordown dedicated one of their Top Tens to 2×2 motos, some pictured right.

You can be sure that one long winter some obscure engineer-farmer has experimented with front-wheel drive long before most of us were born. The vid below is one of many crazy-arsed compilations on youtube. And a couple of years ago Visordown dedicated one of their Top Tens to 2×2 motos, some pictured right.

At that time Visordown said: ... a modern generation of batteries.[…] and hub-mounted electric motors mean that … this must surely be the future of two-wheel drive – allowing almost any bike to be adapted to drive both wheels.

Such predictions proved to be on the money. If AWD is seen to be as desirable as it was when Audi introduced the Quattro road car in the 1980s, then the advent of hub-mounted electric motors is by far the least complicated and most elegant way of doing it. Ask Nasa (above) or even Ferdinand Porsche.

The mechanical or hydraulic solutions powered by an ICE (internal combustion engine), as in the vid above, are mostly just too clumsy, expensive, complex or otherwise lacking in real-world commercial potential.

Off-road the benefits of AWD traction is obvious. I can think of many sandy pistes in the Sahara (above; Algeria) which would have been a whole lot easier and therefore safer to ride with the addition of front-wheel drive. Just like in a 4×4, AWD means you can tackle loose terrain like sandy ruts or dunes without resorting to momentum (aka; speed) which will catch you out (right). And in my experience in the desert, a 4×4 with an automatic gearbox is an unbeatable combination, especially on slow rocky climbs or in soft sand. Just the right amount of torque is fed to all the wheels to give traction, and on rocky trails there is no risk of stalling, again allowing you to concentrate on precise wheel positioning and clearance issues.

Automatic scooters are common, proper motorbikes less so, but do you even need 2×2 on a road bike? The answer is: not really. While road tests affirm that Yamaha’s recent ‘2FW’ Niken (above) delivers eye-opening improvements in front-end grip, on the road 2×2 would only benefit acceleration, by spreading the torque to both wheels and so limiting wheel spin (just as front and rear brakes improve braking all round).

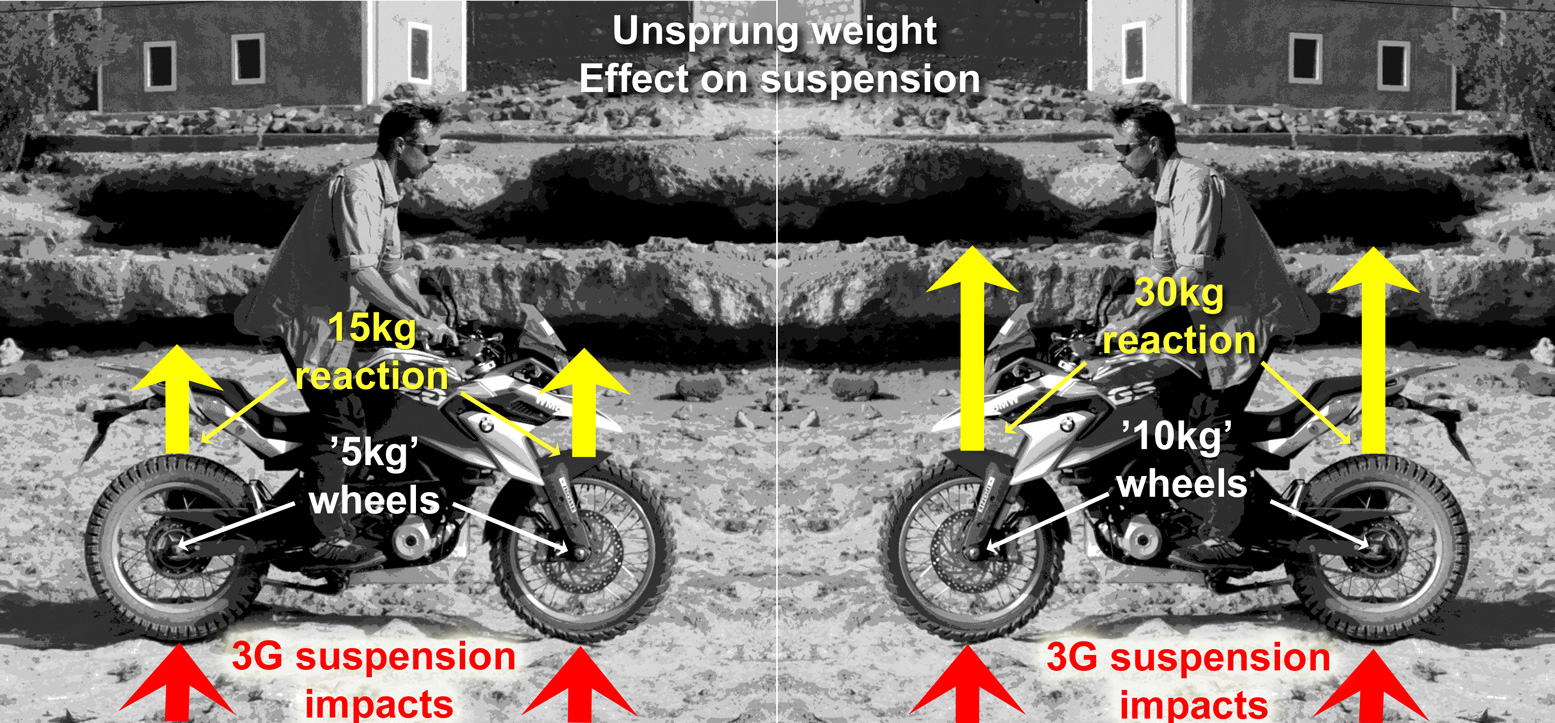

But advances in electronic traction control and tyres to match have proved just as able in optionally eliminating wheel spin. Combined as it is with ABS sensors, TA probably adds just a few ounces to a bike’s weight. Any front-wheel drive system would add several kilos while drawing overall power.

All up, the US-built 200-cc Rokon below is the only successful production 2WD motorcycle – a two-wheeled tractor that looks even less comfortable to drive on anything easier than a wooded hillside and for most people has has probably been superseded by AWD ATVs, even if the latest model features the miracle of front suspension.

UBCO: Electro Glide in White

UBCO stands for Utility Bike Company, founded in 2015 when the work of a couple of creative Kiwi engineers got picked up by entrepreneur, Tim Allan (riding, below).

In 2018, after the original off-road only model had spent a couple of years in development with Kiwi farmers, a fully road-legal, version was released for global export. It’s the world’s first production 2×2 electric motorcycle aimed at farmers, rangers and forestry, while also being bought for urban deliveries and just plain off-road fun. Being restricted to 50kph, it’s classified as a moped which in many territories means it can be ridden on just a provisional licence.

You can add luggage or wider racks and run power tools off it. To recharge the 16-kilo battery takes 6-8 hours. The bike is made in China and in NZ and Australia costs $8000, (about £4200) in the US it’s more. That’s about the same price as a KTM full-suspension e-bike (above right) I saw in an NZ shop window.

Wisely, UBCO dodges competing with the likes of recently folded Alta or Zero who produce(d) full-sized electric road-legal motorcycles. Instead, it’s aiming squarely at the utility market where the benefits of a light, rugged, easy-to-ride and near-silent all-terrain bike outdo its limitations in range and performance.

Weight is 65kg and with 2.4kw (3.2hp) via the 48-Ah, 50-V Lithium-ion battery, power is less than an ICE moped. But 90Nm or 66 ft lbs of torque across two wheel is a figure equivalent an 800cc bike, and all that torque is delivered instantly to each wheel so both will spin as you pull away on loose dirt. Electrotoque is not really comparable with ICE torque: old but interesting article.

Very few electric motorcycles have motors in the wheel hubs. Once you get beyond a moped power level, they become too heavy and bulky so need to return to the typically central ICE location. Above (the two sides of a hub motor), the number and size of copper windings correlate to the power, and these motors are designed to spin fast, hence the three reduction gears on the left. The UBCO’s motors are about as small and low powered as they get on an e-moto, so hub fitting is not a problem. There’s just the low, centrally positioned battery with a power cable reaching out to each hub. Simple.

Tim, myself and his mate JB set off along an overgrown MTB trail at the TECT Trail Park close to Tauranga where UBCO are based. No clutch or gears, no heat, drive chains or belts and virtually noise, plus hydraulic MTB brakes, speed-calibrated regenerative braking and low CoG and seat all make the UBCO effortless to ride. Along with the cleated footrests, it all means you can concentrate on fern-dodging and where to put the front wheel.

Unlike an ICE moto, terrain permitting an electic bike is most efficient with the throttle at the stop and hard acceleration doesn’t consume power like it does on an ICE. Despite its optimal traction and light weight, the low power rating means it’ll only climb 1:4 at which point the short-action throttle is pinned. If you run out of go it’s dead easy to hop off and push. Even with my weight, I found what looks like basic suspension well suited to the bike’s speed potential and the terrain we rode. It’s operation never intruded on my ride and it never bottomed out.

I can’t say I noticed the 2WD, apart from wheel-spinning when pulling away on loose dirt, but it rode as on rails despite the Kenda trials-pattern tyres being at road pressures. The 2×2 has no negative effect on the steering, probably quite the opposite, but you barely notice it. Just like I found myself pressing air for the foot brake, it probably takes a while to believe and then fully exploit the front end’s drive. And no, it won’t be more efficient in one-wheel drive (like old-school 4x4s could be) – the small motors are designed to work most efficiently together. As you can see below, the air-cooled hub motors (the only part of the bike which gets hot) aren’t fazed by shallow water crossings either.

Sure, the MTB handlebars were way too low when standing up, and there was nothing to brace the legs against. But the UBCO is so light and power levels so manageable it didn’t really matter. When sitting down I found my knees banged against the frame, but some trousers or pipe lagging would fix that.

Just like a DCT Honda, the lack of gear changing or fear of stalling really frees the mind to deal with other things, meaning you can ride more smoothly and have more fun doing so. Before I got my current Himalayan I considered adapting a DCT NC750X into something akin to the Rally Raid CB500X. To me this is one of the greatest benefits of electric bikes. Doing the same ninety minutes riding on any sort of ICE dirt bike would have left me comparatively worn out.

The fast-paced off-roading we did would give you about 40 miles range – you’ll get nearly twice that on a flat road at 20mph. And the regen braking means coming down a long pass actually adds a bit of charge. The dash info is basic and includes the temperature of each motor, but you can change or monitor various functions with the bike bluetoothed (or some such) to a smartphone app. Lights are LEDs up to a very bright 2200 lumens.

At the end of the ride I was able to nose the front wheel against the back of the trailer, turn the handle and let it climb up. But even without the 2×2 or even the utility element, like the Sachs moped above, the UBCO can also pass as a cool-looking urban runabout. In the right setting it would be a great way of nipping around without frightening the horses.

In 1967 the Electric Vehicle Association claimed that Britain had more battery-electric vehicles on its roads than the rest of the world put together. Almost all were milk floats (right) rated at around 8-10Kw and with a range of 50-60 miles.

In 1967 the Electric Vehicle Association claimed that Britain had more battery-electric vehicles on its roads than the rest of the world put together. Almost all were milk floats (right) rated at around 8-10Kw and with a range of 50-60 miles.

Even then, the first Golden Age of electric vehicles can be dated back to the start of the 20th century when, in the US for example, 40% of cars were steam-powered, 38% were electric (about 34,000 in total), and just 22% were dirty, smelly, noisy, rough-running ICEs. Then major oil fields were discovered around the world and before domestic air travel became the norm, the interstate road network went on to outstrip the railroads. Now there are well over a billion ICE road vehicles in the world, about 20% of which are bikes. The total number of EVs surpassed 3 million in 2018, a 50% increase over 2016.

Electric Bikes

The future will be electric, again. That may well be the case in urban settings or for other short-range applications. In 2008, alongside the more common pushbikes I was amazed to see electric scooters (right) whooshing around the streets of Kashgar, western China. And in Auckland last week I was equally intrigued to see dock-free e-scooters (left) either left on the pavement or whizzing about between pedestrians.

But any form of trans-continental overlanding in the less-rich AMZone will probably be the last place to see e-motos. The world is just too divided between rich and poor, urban or rural. Just as with fast internet or mobile phone masts, the cost of installing the necessary infrastructure everywhere is too great. It’s an overlanding quandary which has become analogous with diesel cars. Low-emission engines designed to run the low-sulphur fuel sold in rich countries will play up on the old, high-sulphur stuff sold in some parts of South America, Africa and Asia where emission regs are less strict and ‘Euro 5’ is a football tournament. So while in the next decade you might be able to ride your e-moto across Europe or North America, as things stand Cairo to Cape or Prudhoe Bay to Ushuaia will be a challenge for a long while.

Visualising a sunshine-powered, off-road coast-to-coast traverse of Australia, similar to their World Solar Challenge race, I asked the UBCO tech guy would the necessary 400-w solar trailer (about two panels on the left) do the job? No. A battery can’t be charged and discharged at the same time, but a spare battery could be charged. Broome to Adelaide at 30mph max would sure give you plenty of time to get a nice sun tan.

Some say the specific problem with electric motorcycles (as opposed to e-bikes, cars or trams) is that, price apart, with the available technology the weight vs power or range doesn’t add up with current perceived expectations of what a motorcycle can do. It ends up either too heavy, too slow or runs out of charge too soon. But even Harley’s turbine-smooth Livewire (above) only weighs 210kg, does 0-60 like a 701 and might last 100 miles. We’ll know more (or not) when the Long Way Up comes out this autumn. Other electric bikes will do better. As we approach the fabled Tipping Point you’d hope things can only get better.