See also:

Chinese travel bikes article

Royal Enfield Himalayan

Updated 2020

For a while there was a bike I was curious about: the French-branded, Chinese-made Mash Adventure 400 (left) that was briefly available in France and the UK alongside other 400s. It was near identical to the similarly short-lived WK Trail 400 mentioned here. Both use the same Shineray XY 400 engine from Mash’s Roadstar retro.

For a while there was a bike I was curious about: the French-branded, Chinese-made Mash Adventure 400 (left) that was briefly available in France and the UK alongside other 400s. It was near identical to the similarly short-lived WK Trail 400 mentioned here. Both use the same Shineray XY 400 engine from Mash’s Roadstar retro.

In the UK you could pick up low-mileage WKs from £2500 and end-of-line Mash Advs were going new from £4750, complete with panniers.

Other than the engine, those two Advs were quite different to the Mash 400 Roadstar I tried out (above). The frame’s monoshock back-end and bigger front forks made a much taller machine; both ends were said to be fully adjustable; the wheels are 18/21 and both run discs. There’s a bash plate, screen, handguards and digital clocks plus the mandatory beak.

The WK Trail 400 (left) was briefly sold in the UK and a couple of magazines, including Overland Mag and Rust Sports tested it. Its price dropped from around £4k to a more realistic £2999 £2499 before they all went.

I spent about four hours on the Mash Roadstar provided by T Northeast, a small bike shop in Horley, near Gatwick (they no longer sell the 400s and Mash UK seems to have closed). The bike only had about 150km on the clock and I added another 120km riding the back lanes of Sussex and Kent.

Some specs

Engine: air-cooled 397cc SOHC 4 valve, EFI, electric and kick

Power: 26–29hp (sources vary) @ 7000 rp

Torque: 30Nm @ 5500rpm

Weight: 151kg claimed

Alternator output: unknown

Seat height: 78cm/31″

Fuel tank: 13 litres

Wheel size: 18″/19″

Brakes: drum rear, hydraulic disc front

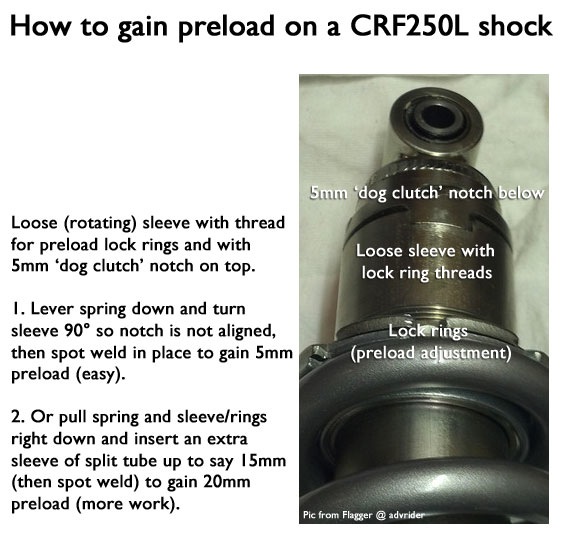

Suspension: twin shock with preload, 35mm fork

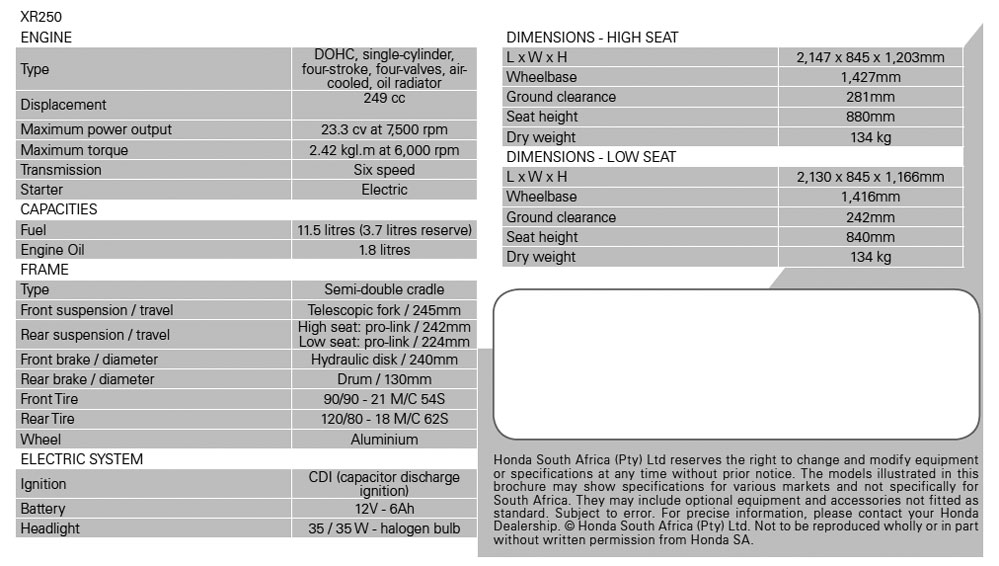

For comparison

• Honda XR400: 31hp and 32Nm @5500, 130kg

• XBR500 43hp, 43Nm @6000, 167kg

• Yamaha’s short-lived SR400 23hp, 27Nm @ 3000rpm and 174kg

• Himalayan 24hp, 32Nm @4500 and 192kg

• Saturn V space rocket 10.6 million Nm @ sea level, 496,200kg

The Mash Roadstar is a great looking machine with an idealised Brit-retro ‘T120’ (left) profile that’s as cool as the originals it’s imitating. The flat bench seat, fork gaiters, peashooter pipes all set off the right cues.

You’d think it’s small but that’s mainly because it’s low. It fitted me (6′ 1″) fine: the footrests felt farther forward than normal with my thighs almost horizontal and me sat midway on the seat. I didn’t get a picture of myself sat on the machine – had I done that the proportions may not have looked as flattering as they felt. The gear lever was a bit short for my boots, but changing was light and near-silent compared to the granny-startling clunk into first on my Versys or my previous XCountry. Though it’s not a habit I’ve ever managed to maintain, clutchless changes up the ‘box were similarly effortless with no backlash.

The switchgear didn’t quite give off that intangible feeling of solidness and quality you get from your Japanese or European machines, though all I used were the indicators. The headlamp is always on, though you slide a switch to turn the back light on.

The Mash Roadstar resembles Yamaha’s UK-reintroduced but soon dropped SR400 (left). The mini SR never caught on, despite the retro trend. First time round in the late 70s the original SR500 wasn’t such a big hit either, while the XT500 with which it shared its motor had already become the classic it remains today. Alongside the Roadstar, the £5200 SR400 merely looked overpriced and heavy. What it needs is some of this!

Back at T Northeast I was warned the front brake was poor – a braided hose is said to be in the works. It was lame but over the hours I found applying more pressure than I’m used made it work like a normal brake. Of course you lose finesse yanking on a brake like that, and I’m not sure that can be purely down to a cheap rubber hose. The rear, rod-operated drum was fine and I dare say would lock up with a panic stomp. One old trick we used to do was remove the brake rod and put a light bend in it to reduce the over-direct actuation. Wheels are your classic 18/19 combo and the Kenda Cruiser tyres hardly got stressed on my ride. There was a downpour on the way back but riding with the conditions, they didn’t skip a beat.

Initially riding away from the shop the bike felt as skimpy as a 125. This lack of bulk and the airy front end detracted from the planted feeling on my Versys (at the time), but that can’t all be down to an extra 70-odd kilos of weight. It could be due to the spindly 35-mm forks alongside the proportionally hefty front wheel.

The suspension is basic on the Roadstar. Out of the shop on notch 2/5, my dressed-to-ride 100 kilos bottomed out the back-end on country-lane potholes until I cranked them up to 4/5 with some pliers I happened to have on me (no tool kit that I could find). It’s possible the steering feel improved on doing this too, or maybe I was just getting used to the bike. It takes some effort not to compare a new bike to your normal ride, even if it’s another type of machine entirely.

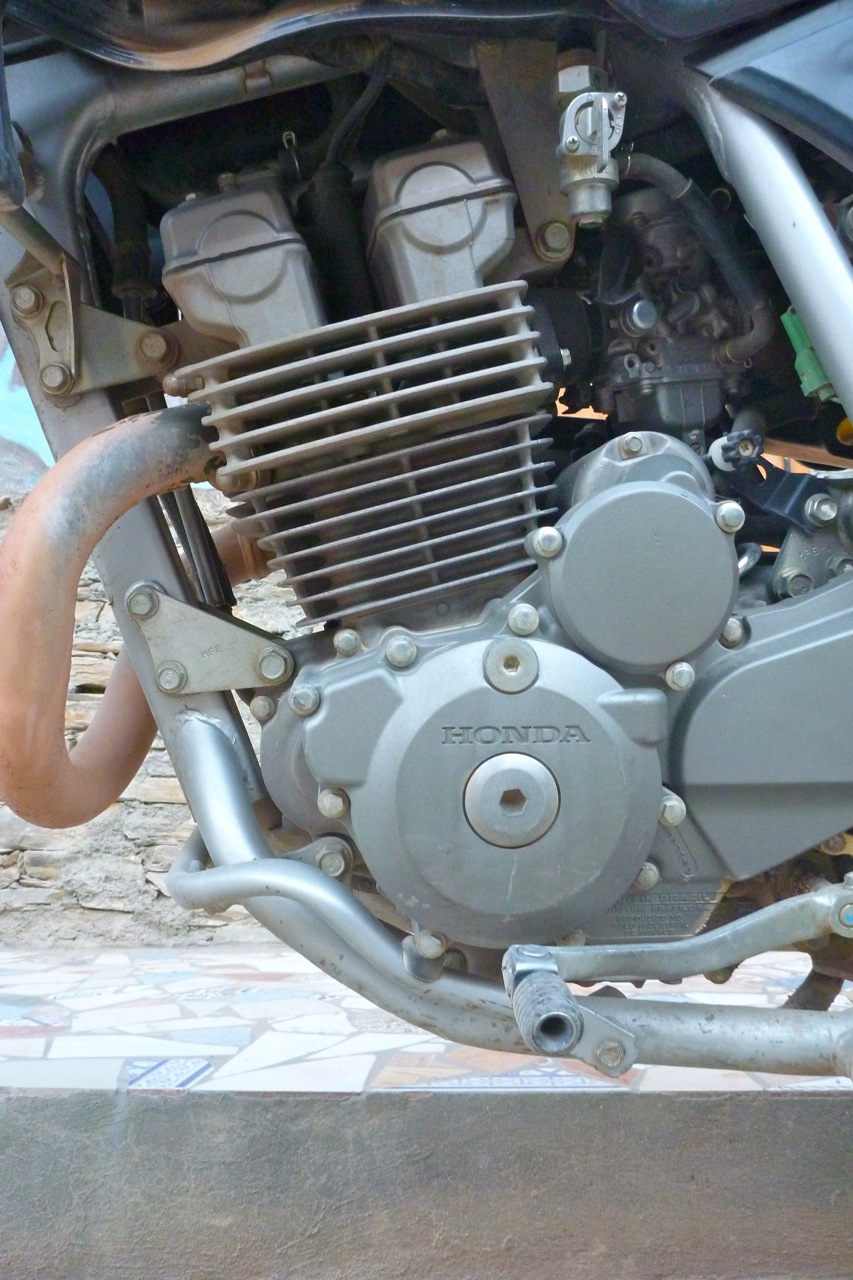

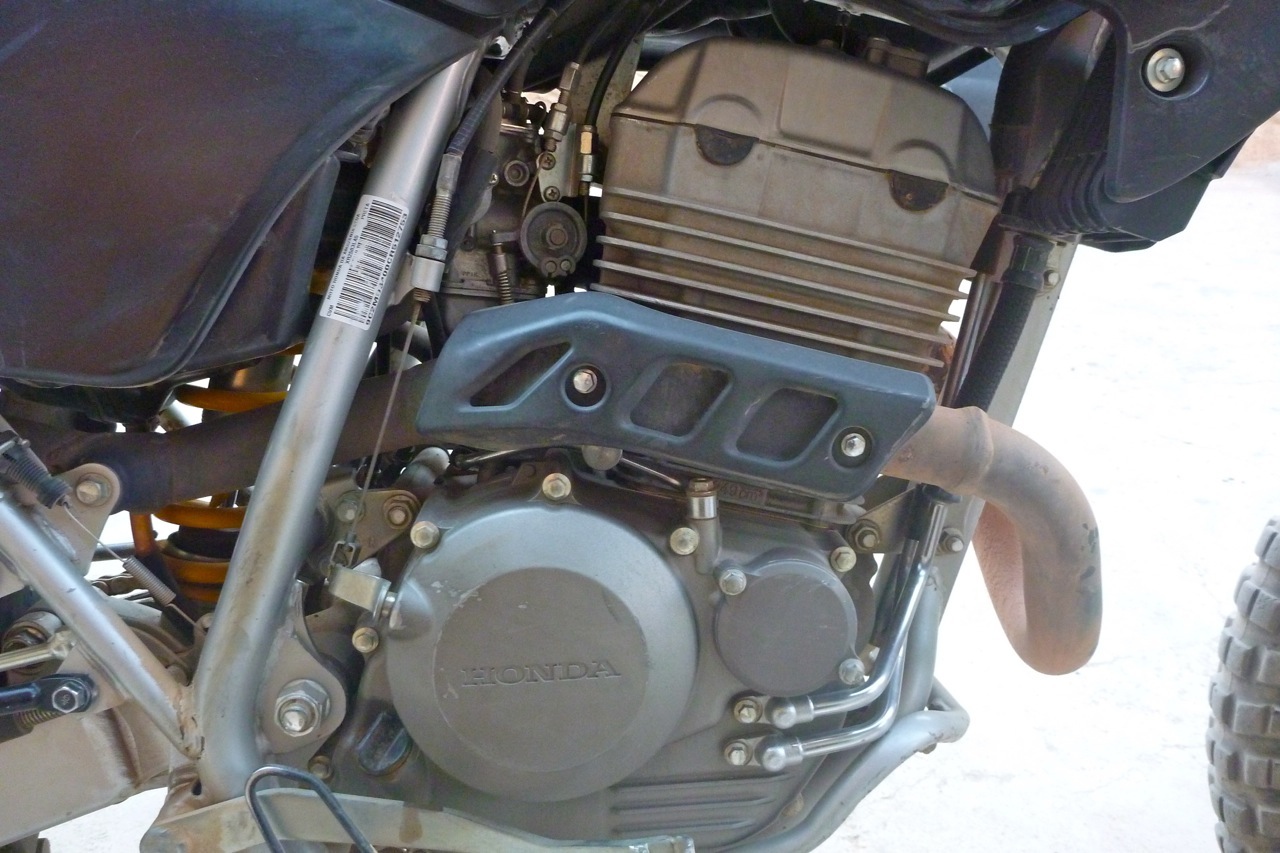

I know the Roadstar is low but the bike does feel very light and I wonder if that claimed 151-kg figure could be wet. My XCo was supposedly just a few kilos over that weight before I layered on the travel clobber, but the Roadstar felt more like my CRF250L (144kg wet).

And it’s not like the Roadstar goes out of its way to save the kilos. Just like the bikes from the period it evokes, sidepanels, mudguards and the chain stay are all metal. Even the oil tank sat behind the gearbox (left) looks like an unusually hefty casting and the chain this bikes runs is much heavier than what’s on my Versys with more than twice the power.

It may well be a Chinese cheapie, but once that’s shot and you slap on a DID I can imagine it would easily last 20,000 miles with something like a Tutoro drip luber. Along with the low seat height, this lightness has great benefits in doing a quick u-ey to nip back for a self-timed photo or follow a lane that looked like it went somewhere good. I had a delivery in Kent, but as there was no 12-volt plug to run a satnav I was navigating the old-fashioned way with a cryptically scrawled roadbook taped to the tank.

Running along Kent’s lanes at up to 50mph (clock and odo in km with mph scale on the speedo) the bike ran well, though I’m not sure I was doing the indicated speed. Push it to 60 and you start to ponder the limits of the brakes and suspension.

The five-speed gearing felt wide and tall: top gear was more of an overdrive rather than something with which you could usefully pull. It could be the very low mileage, but the Roadstar didn’t feel like it could have outrun my CRF250 or the XR250 Tornados we used in Morocco. And I’d expect to feel that power right off the bat, not by wringing the bike’s neck like it was a mid-80s two-stroke triple. For me the point of tracking down a 400 over the much more prolific 250s is either gaining a lack of balls-to-the-wall revviness or the ability to pull in lower gears with fewer gearchanges, but all without the weight penalties you get once you exceed 500cc. I was changing gear around 4000rpm – to rev much further would have felt a bit frenetic and unnecessary, but the 26-hp Roadstar’s motor felt more Jap 250 than XR400, let alone my old XT500 (below) which is listed as 27–31hp but 39Nm torque at broadly similar rpm. Another few hundred kilometres on the engine may have changed that, or it could be down to flywheel weight or the stroke of the motor. Mash don’t mention it, but the WK lists an identical bore and stroke to an XR400 just 0.4 bar less compression (8.9 vs 9.3). These are all just numbers off the internet where I found claimed power and weigh figures can vary by over 10 per cent for the same bike.

Whatever the style of bike, one big attraction is fuel injection combined with a low-compression, air-cooled motor onto which it would be easy to graft an oil cooler. That might not be necessary or all that effective as with 8.9:1 compression ratio and the lowly power output, this 400 ought not get that hot in normal conditions. The low compression also means the motor ought to tolerate low-octane fuel out in the world, though I’ve found efi systems on big singles like the XCo and 660Z Tenere can handle detonation from low octane fuel, whatever the engine’s CR. Another benefit of all this is should be fuel consumption. I filled up at the start but forgot to fill up again at the end to work out what I used, but surely the retro Masher will return at least 25kpl or 71mpg. With the 13-litre tank that would deliver a fuel range of some 325 kilometres or 200 miles – about 80% of what I’d consider optimal for a travel bike.

You might get used to the modest power but the main thing that would limit an adventurised Roadstar would be the suspension. At 35mm the unadjustable forks look skinny even if the preload-only twin shocks could be swapped out. The metal chain guard and front mudguard would be better in plastic too and the low-slung pipes as well as the under-engine oil lines would need protecting or moving over the top like an XBR. Without crash bars the foot controls might suffer in a fall too; the gear change could be easily swapped for a folding-tip item, but doing the same with the brake pedal would be tricky to pull off.

One good thing about being twin-shock is you could get away with using throwovers without a rack to keep them out of the wheel. The little racklette (right) that comes with the bike is neither here nor there – I’d sooner take it off and fit a wide sheep rack as I did on the XCo. I couldn’t work out how to remove the seat other than with an awkwardly accessed 12mm, and only managed to remove one side panel, but the subframe does seem well up to the job compared to 250 trail bikes like the CRF and Tornado where it’s their biggest weak point. The Roadstar chassis has thick gussets inside the triangulated sections and, though slender by monoshock standards, the long swingarm looks solidly mounted via the back of the gearbox.

I did something on the Roadstar I’ve not done on a bike for many, many years: swung a kickstart. I assumed the Mash would kick into life like a CG125 with one swing, but it seems I’ve lost the knack and it took a few stomps to the point where I lost interest in doing it ‘for old times’ sake’.

I recall how we lamented the dropping of kickstarts from motorcycle engines, but then and now a button just gets the your motor running. And should the Mash not start on the button I bet it would take a lot of huffing and puffing to fire up an engine with a kick. It’s been discussed before but a weak battery is likely not to have the spare juice to power up the efi and fuel pump as well as fire a juicy spark across the plug. Better to just do a jump start.

My parting impression of the Roadstar was of a bike whose welcome lightness makes it effortless to ride along quite roads and in town, but which on the open road looked a bit better than it went. Compared to a 250, I didn’t get a sense of any added grunt from the 400cc motor, even if it wasn’t a revvy machine.

In 2018 I finally got to ride an XR400 – you definitely know you’re not on a 250. And that’s as it should be and why 400s are an overlooked ‘missing link’. Actually no so ‘missing’ as ‘not here’. Bikes like the Brazilian-built carb’d NX4 Falcon (above) went for £4000 new in Mexico, or the 250 Tornado never officially imported to emissions-conscious western markets.

The Roadstar’s widely spaced gears would need working to move along, though you’d want to get that front brake sorted first. The saddle probably wouldn’t sustain a day’s riding, but then even with a screen, the Roadstar isn’t intended for that sort of use and there are much more sophisticated bikes with truly terrible seats.

As for the price [at the time of testing]? Even with the warranty I still think nearly four grand in on the high side for a basically equipped Chinese 400 single. If it follows the UK imported and branded Honley 250 Venturer, that price may well drop after a while [still €4000 in 2020), because as things stand the depreciation on a used Chinese branded bike will surely be monumental. Otherwise, for that money I can take my pick from a used CB500X or buy any 250 I want.

Motorbike capacities come with certain expectations and on this test ride it was the 400cc engine I was keen to assess. In terms of more-than-250cc grunt, the Roadstar was a bit disappointing or perhaps just needed more running in. Add it all up and as a low-tech adventure tourer I think the Roadstar is a bit too basic for the money. You can pick up used low-mile Roadsters on eBay from around £3000 so the depreciation isn’t that bad, but in 2019, my same-priced Himalayan ticked more boxes.

Thanks to Ian at T Northeast for the test ride on the Roadstar.