Buy Desert Travels 2021 on Amazon

Did you miss Part 1?

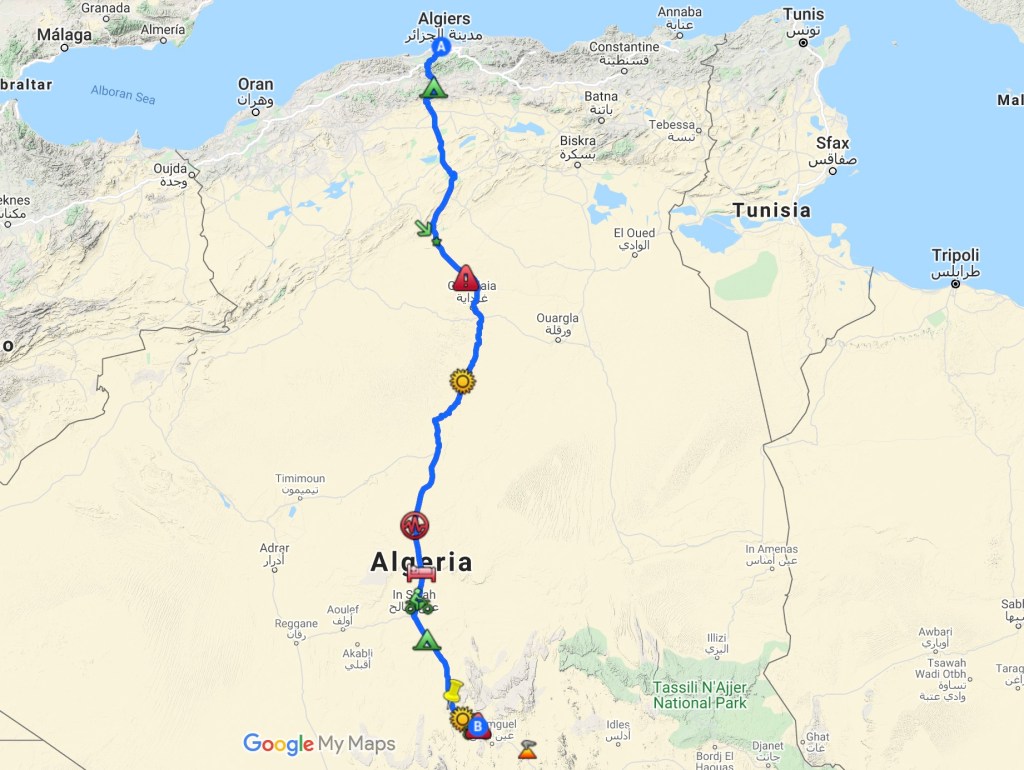

Recap: I’m taking a two-week touring holiday in Algeria, late summer 1984, and it has become very hot indeed. I’m riding a 200cc mash-up of AJS, Honda CD200, VW and Yamaha, with enough ground clearance to become an Olympic sport, but barely enough power to stir a tea bag.

Yesterday I rode through a tornado and right now I’m just south of the Tademait plateau: it’s Day 3 in Algeria.

This is part two of a bonus chapter which does not appear in the book.

I got up before sunrise but it was still as warm as a hot summer’s day in the UK. I packed up and rode towards In Salah, a hour or so down the road.

Soon I came across a French guy on a Z750LTD – that’s a Kawasaki early 80s mock-chop in case you’ve forgotten. Clearly, 1984 was the year to ride the Sahara on dumb bikes.

He was sat by the side of the road looking a bit how I felt: shell shocked. Yesterday on the Tademait, the sand storms had also freaked him out too and he was beginning to realise his spine-wrecking ‘factory custom’ was not such a cool highway cruiser after all. He’d had enough and was heading back north.

I carried on south, passing the denuded outliers of the Tademait plateau.

The old fuel station in In Salah was always fighting to keep its chin above the sands, and I pulled in to fill up for the next stage: 270km along the Trans Sahara Highway to Arak Gorge with not so much as a well on the way.

A short distance out of town I passed another fallen truck, as I’d done near here in 1982 in the XT, only that time it had been flat on its back with its wheels were up in the air.

As before, the road was perfectly flat and straight. You presume the driver dozed off in the heat of his cab and jack-knifed.

It’s not the greatest picture I’ve ever taken but you’ll notice there’s someone camped by the truck’s under-carriage. He’s watching the wreck so it doesn’t get stripped bare before someone comes along with whatever it takes to get it back on its wheels.

Time for a quick pose why not. Young kids these days think they invented self obsession and selfies! We were doing that years ago!

I liked my trusty Bell Moto 3 but I’m sure glad I never had a crash in it. The padding inside was about as inviting as the inside of a cylinder head. I also see I’m wearing a natty nylon British Airways cabin steward’s scarf picked up in Laurence Corner’s army surplus ‘boutique’ in Camden, just up the road from our Blooomsbury squat.

Bell ’84

Bell 2020

They say the Beatles bought their Sgt. Pepper outfits there, and the likes of, Adam Ant, Kate Moss and Jean-Paul Gaultier have all rummaged around in the junk at LC, looking for something to cut a dash. As trendy London despatchers looking for the ultimate outfit, we did too, and I think the scarf was an impulsive £1 purchase.

Decades later Bell brought back the Moto 3, but with a 21st-century velvety interior.

Back to the desert where the only fashion was to get to the next water before what you had ran out. The low elevation hereabouts meant it was becoming exceedingly hot. I’m guessing about 45°C or over 110 F.

That’s nothing unusual at these latitudes I’m sure, but I’d never experienced temperatures like this. I was being baked alive by the air I was riding through, and so I wrapped up tight to keep the blast from turning me into a shrivelled Peruvian mummy.

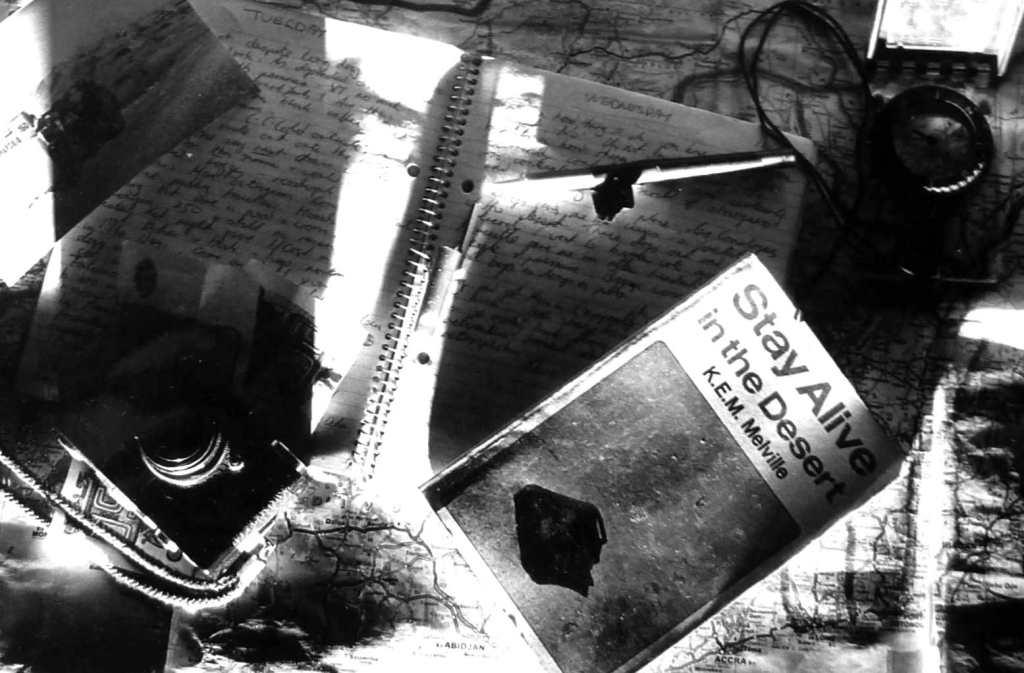

In this pre-Camelbak era, every half hour or so I just had to stop for a drink. I was getting through water at a rate of 10+ litres a day. As I rode along, by the time I could stand it no more I’d feel the desiccation creeping down my throat. I realised how fatal dehydration actually gets you: from the insides out as you helplessly breath in air at well over body temperature (36°C). The survival manuals were right all along: without water or shelter, consciousness could be measured in a matter of hours in this sort of heat.

At one point I thought I simply must cool myself down and poured a helmet’s worth of water into my Bell and put it on. The delicious deluge soaked down through my clothes with a steamy hiss. But half an hour later I was again throat-parched and dry as a roadside baguette.

The Trans-Sahara Highway that had finally linked Algiers with Tamanrasset just a couple of years earlier was already breaking up, and in this heat, you could see why. Black tar which sizzled as you spat on it wouldn’t stand a chance as another over-loaded lorry hammered the scorching highway to a pulp.

Diversions shoved traffic onto the sands so repairs could be undertaken, and I had my first chance to be forced to ride the Benele off road. All things considered it managed well enough, even with horsepower barely into double figures. The trials tyres and light baggage all helped.

Then, as I neared the Arak Gorge something changed in the ride, the suspension seemed to tighten up. I hopped off, dreading some problem with the Honda motor which could surely not handle such heat for much longer. It was a simpering commuter hack brutally abused by being thrown into the deep end of a Saharan summer.

A quick look revealed the chain was as tight as a bow string. On this trip I was experimenting running a non-o-ring chain dry to avoid oily sand wrecking the seals. I can tell you now that was a bad idea. Years later I rode a BM in Morocco with an o-ring that got plastered in sand, and even with daily oiling it needed adjustment just once in 4000 miles. The lack of lube and high ambient temps had caused the dry chain to somehow shrink – perhaps the rollers expanded and took up the slack.

Modern bike chains are incredible when you think what they do, but back then I was worried my hyper-taught chain and bouncing suspension – three times longer than any CD200 had imagined in its worse malarial dream – might rip out the engine sprocket and ping it across the desert floor like a Coke bottle cap. I soothed the creaking chain with engine oil and watched it sag before my eyes. Now it was way too slack but the AJS frame had some nutty eccentric swingarm pivot like 1970s Ducatis which was a faff to adjust in the state I was in.

I was out of water and the mercury was again pushing at the end of the dial. Just as I’d panicked when my XT500 had leaked away half its fuel on the way to Niger in ’82, I felt the compulsion to flee towards shelter so rode on to Arak just a few miles down the road, with a slap-slapping chain.

Relieved I’d just caught a bike catastrophe in time, I decided to remount the closed-off blacktop under repair to save any strain on the transmission. The gorge walls of Arak rose up ahead, but then the tar suddenly took on a darker shine and I sunk into a sludge of thick, freshly laid bitumen as the gutless Benele lurched to a crawl. I yanked on the throttle to spur the slug onward, the tyres pushed a trench through the oily slush and bitumen sprayed up across the mudguards with a clatter of sticky gravel. What a mess. I steered off the unset mush and continued to the roadhouse, hoping my tar trench would melt back smooth again, like divided custard.

Now safely at the roadhouse I crouched in the shade clutching a drink and looked forward to a rest before the final stage on to the Cone Mountains, 100km on where the desert landscape begins to get interesting. As I pondered my near miss with wrecking the bike, an army jeep pulled up, two guys jumped out and marched up to me.

‘Is this your moto?’

‘Yes.’

‘Why did you drive on the closed road!’

I pathetically tried to play dumb until they pointed our the sticky black splat coating the undersides of my bike.

‘I am sorry. I was panicking. You see my chain was…’

‘Shut up. Did you not see the signs ‘Road Closed? and the stones blocking the road’

‘Yes. Sorry. Look I will go back and repair it myself’, I reasoned, thinking I could smooth it all back with a plank of wood.

‘I said shut up! You will pay for this. Give me your passport!’

One snatched it out of my had and they tore off back to the fort in a flurry of wheel-spin. The other people in the roadhouse looked down at me with the pity of one who was rightly in the dog house, gagged up and tied down. Another heat-frazzled wannabe adventurer disrespecting locals regs. There began my three day ‘hut arrest’ in Arak.

Everything I had was hot. Nothing had cooled down for days. As I unpacked my stuff I found candles drooped into Dali-esque blobs and weirder still, opening a tin of luncheon meat or ‘Spam’, the contents poured out like water, flecked with pink particles of fat-saturated gristle. I’ve not eaten that shit since.

I spent the days reading J. P. Donleavy or chatting with other similarly heat-struck bikers passing through, while dust storms periodically ripped through the gorge. By night it was just too stifling inside the hut, so I slept outside in what little breeze there was. Even then, I’d wake up once in a while with my lips and throat parched fit to crack, and struggle to douse my mouth from the water bottle.

As the days passed I knew I was running out of time to visit my goal: the mini massif I now know as Sli Edrar (below).

Then one morning the army jeep returned with my passport with nothing more than an admonition to not do it again. Ashamed of my stupidity, I’d got off lightly and vowed to oil the chain as often as it damn well liked.

I packed my ragged bags and set off on the 1000-mile ride back to Algiers port where a boat left in three days’ time.

A day or so later I wasn’t feeling well. I got past In Salah and found myself lightheaded and weak. Just up ahead was the climb back onto the dreaded Tademait plateau, not a place I wanted to tackle in the shape I was in. So halfway up the switchback ascent I pulled off the road and crawled into the shade of a metre-high culvert.

What was wrong with me? I was surely drinking enough: 10 litres a day and a couple more by night. Then it struck me. Water was not enough. I needed to ingest salt and other essential minerals flushed out in my sweat which evaporated unseen. That must be it. I made myself a salty-sugary drink and lay back while it took effect, wary that this was just the sort of place snakes and scorpions might also like to pass a siesta.

Despite, or perhaps because of my dozy state, I clearly thought a picture of my other camera on a tripod would be a fitting souvenir of my in-culvert recuperation.

The drink (1 spoon salt, 8 spoons sugar per litre) quickly did the trick and revived, I set off across the Tademait, tensed up in readiness for something bad to happen – a piece of the sky falling on my head, perhaps? Nagging me were the 1100km that still lay between me and the Algiers boat. It was time to lay down some miles.

For once the 400-km crossing of the the Tademait passed without event which in itself felt creepy. I filled up in El Golea and another few hours got me past Ghardaia, the gateway from the Sahara. Only now it was late afternoon, time for the headwinds to kick up. At times the feeble motor strained to reach 25mph while I crouched over the bars, crippled with stiffness, watching the odometer numbers click by in slow motion.

By this stage the UV had seen to my thin cotton Times delivery bag which had fallen apart. I lashed it to the bike with a piece of plank and some nice 7mm climbing rope.

Around Berriane the rising heat from the south sucked in a dust storm and visibility dropped to a few feet. I edged to the side of the road, wondering if I should get off it altogether, not least because cars still rushed past, confident that whatever risk they took, it was OK because All Was Written.

By Laghouat I’d chewed a good 1100-km chunk out of the map. I unclawed my hands from the ‘bars and hobbled into the only hotel in town. But the uppity ponce behind reception had no room for the likes of me, so I rode out to some edge-of-town wasteland. As I slumped against a litter-strewn, shit-riddled ruin, a guy living in a cardboard hovel I’d not even noticed hailed me over.

I’d never actually met a regular Algerian civilian. He invited me in and we chatted as well we could while his unseen wife prepared a meal. He proudly told me how was a veteran of the recent Western Sahara war against Morocco (Algeria lost that one and it eats them up to this day) and gave me a picture. When the time came I was invited to sleep on his living room carpet.

Sadly, the carpet turned out to be agonisingly flee-ridden and try as I might and worn out as I was, I couldn’t drop off as another bug took a jab. I moved out into the donkey yard but it was too late, the fleas had latched on and in turn went on to infest my favourite mattress back in my London squat for months. I did everything I could to delouse it, repeated dousing with flea powder and even gently torching it with hairspray and a lighter. But as the flames licked over it, those Algerian bloodsuckers just yawned and sharpened their mandibles. Eventually I had to chuck it.

Leaving Laghouat next day, I passed billboards of whichever corrupt Big Brother was dictating over Algeria at the time, and just out of town I found the time to wander up to Pigeon Rocks, not realising they were the site of prehistoric etchings.

Thanks to the killer, 12-hour, day from Arak, only 400kms remained to the port. I was well on target to catch the boat at noon tomorrow. After a week of relentless day and night heat, the temperatures finally began to subside as I rose into the Atlas mountains north of Ain Oussera.

Late afternoon, unready to face the congested capital, I bought myself a roadside melon and bounced over some roadside scrub down into a ditch, stalled the bike, and passed the night there.

Another big mistake. I’d carelessly left the ignition on after stalling the bike (something I’ve caught myself doing since, when dirt camping). Next morning the battery was as dead as week-old roadkill and, try as I might, no amount of jump starting could get the Benele going.

It was just 100km to the port with hours before the ferry left. I pushed the bike into a lay by, made a sign ‘Alger port SVP’ and eventually two kind blokes responded to my plea and loaded the Benele into their pickup.

’What’s with this tar all over the bike?’

Don’t ask, mate…

Following a battery acid transfusion and a cafe noire injection in Medea, I was good to go. I spun down the Atlas bends into Algiers and blundered my way to the port gates. I was late but so was the ferry.

Even today I can tell you: nothing beats the feeling of a ferry steaming away from a North African port. Did I say that already about the 1982 trip? Well, it was even more true in 1984 and on most years since. Let Somali pirates steal us to their thorny lairs; let sudden storms rain down hail and brimstone. I was out of Algeria. Yippey–aye-yay!

A day later the boat docked at Marseille. It was probably Friday and I had to be back at work on Monday. So I’m still not sure what possessed me to make a casual visit to the Bol d’Or 24-hour endurance race scheduled for that weekend nearby at Le Castellet raceway. Maybe I had some energy to spare. Bike magazine had enshrined the Bol as a biker’s rite of passage – France’s one-day equivalent to the Isle of Man or Daytona; as much a moto-carnival as a race spectacle.

I rode in and watched the 3-man teams flip their slick-tyred UJM’s from bend to bend and also enjoyed some baffled looks at my bike, battle scarred from its recent desert detour. The trail-bike loving Frenchies, who went on to buy more Ténérés than anyone else, at least would get something like Le Bénélé.

Heads down for the Mistral straight

Wandering above the pits, I even had the presence of mind to check out #53: an RD500LC popping in for a fill up. I bet that team spent more time filling the tank than the rider did on the track.

But my abiding memory from the ’84 Bol was a vision of my desert biking future. In fact it was a future that was already two years old, and its name was Yamaha. XT600Z. Ténéré.

On the Sonauto Yamaha stand was TT-Z Dakar factory racer looking slick in the sexy, pale blue Gauloise livery (left) which we never got in the UK. The desert racer had it all: 55-litre tank, discs all round, 12-volt lights and a side stand as long as your arm. Even if the road-going XT-Z was less extreme, what was not to like?

My Bénélé joke-bike had been a cocky two-fingers flicked at the Yam. Why? Search me, but 30 years later I found myself engaged in a similarly pointless project.

More cool early Dakar racers here

OK, I concede. The Tenere ticked all the boxes, but it had been fun doing it my way. I’m sure there’s some pithy Armenian proverb that spells it all out, something like:

‘The eagle never lost so much time as when he submitted to learn from the crow‘.

Actually that’s William Blake as quoted in Dead Man movie.

Anyway, a Tenere could (and did) come later, right now It was time for the final haul, another 1100 clickety-clicks to Calais and a boat back to the UK.

I spent that night in some slug-riddled forest, and Sunday morning saddled up bright and early to get a good run up for the ferry ramp. Tonight I’d be back home, but as I’ve learned so well over the years: it’s never over till it’s over.

I don’t know where I was – the middle of France somewhere – but within an hour or two of setting off, a slate-grey death cloud crawled up onto the horizon, unzipped itself, and with a shrug proceeded to empty its bladder right in my face. My desert desiccated leathers soaked up what they could, before passing it onto my next layer of clothing, until within just a few minutes I was a sodden spongebag of saturated rags.

Splashing through a village, I overcame my Britannic reserve, swung into a farmyard and rode the bike into a barn. Inside was an old steam-powered lettuce thrasher. There I slumped, dripping on a workbench, exhaustion welling up from the previous fortnight’s moto mania. I was dropping off and ready to tip over in a heap when the farmer wandered in and said dryly:

‘Fatiguée, eh?’

I perked up with glazed eyes and luckily looked the part of a road-weary, waterproof-scorning wayfarer, rather than some deviant trespasser. He let me be.

Later that afternoon the P&O ferry disgorged me at the end of the A2 which reeled me back into London. Spinning along at 45-50, clogging up the slow lane, I snapped this defiant shadow shot as I went by.

Back home, what the Germans call der durchfall began to form, as my shrunken stomach reacted violently with longed-for snacks. My drenched leather coat fell to the floor with a squelchy thud and I was surprised to see there were still dry patches on some parts of my clothes.

I had just enough energy left in me to glare at the camera which had become my cherished companion this last fortnight and snarl like an alcoholic on New Year’s Day:

No more sodding motorbikes! Ever!

Well, not until 8am tomorrow, that is.

Buy Desert Travels 2021 on Amazon