Originally published in Motorcycle Monthly in 2012, I just dug this out from the archive. It’s of interest as it describes how I came to choose the meaty part of Stage K of today’s Trans Morocco Trail, one of the trickier desert sections of the coast-to-coast ride. There’s more on the F650GS here. For a big bike I quite liked it. Long, low and easy to live with, as they nearly used to say.

There’s always a sense of trepidation when you set off alone on an unknown desert track on an untried bike. The bike’s performance and set-up are added uncertainties. I’d done the first few miles of this route before, but once the creek passed a well and took a gnarly climb onto an escarpment I was on new ground.

Left led north: I’d done that one before and had recently read about a guy on a DR who’d fried his clutch and in a panic called the British Embassy for help. A complicated and costly recovery followed. Hoping for better luck, I took the right fork towards the Algerian border. The coarse limestone bedrock kept speeds down, but the way was clear.

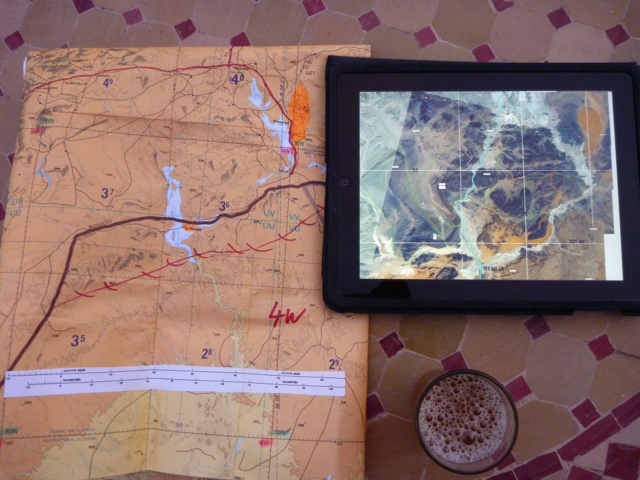

Up ahead flat-topped hills stacked up to the northeast but soon the helpful line of the Olaf [early digital] map dropped off the screen and I was back to pre-GPS nav, watching my orientation and seeking the most used track.

My plan for the second edition of my Morocco Overland guidebook was to sweep across the Kingdom from the east, much like the Muslim hordes some 1300 years ago, but causing much less of a disturbance. I’d log new routes from the Rekkam plateau in the east to the Reguibat tribal outlands of the Western Sahara, adding whatever took my fancy along the way.

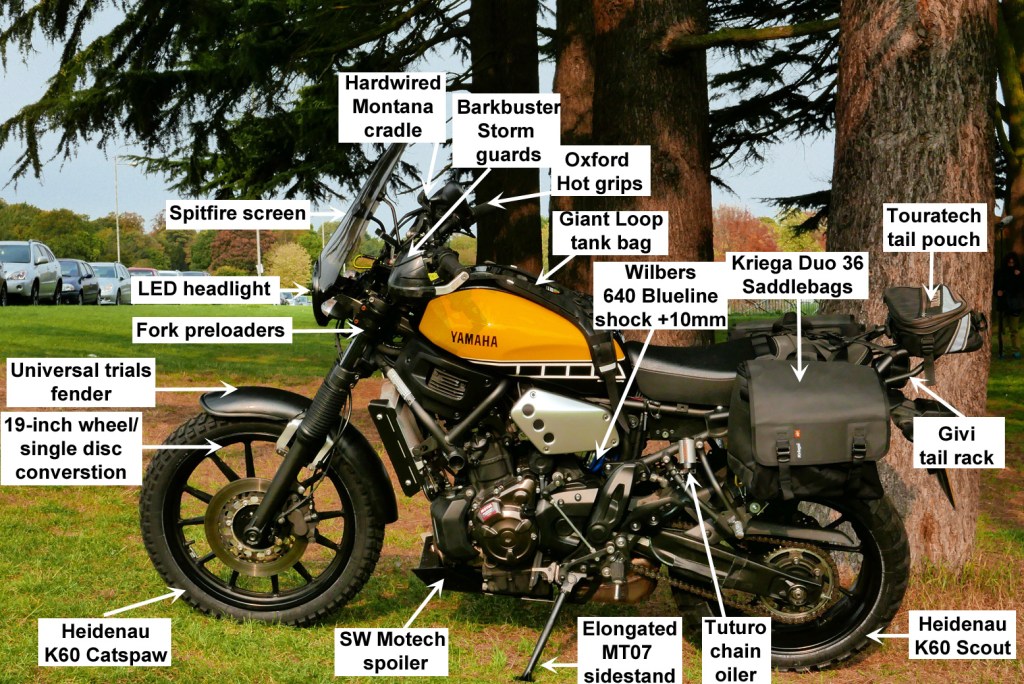

My own Suzuki GS500-based overlander was barely complete so I planned to rent out of Marrakech, but BMW Motorrad UK stepped up with a new F650GS SE twin, the modern iteration of my Suzuki project. According to my calculations the 650 ought to be the ideal Moroccan tourer: fast and comfy enough to bang out the

European stage, and an adequate dirt tracker once I got there.

Enter sand man

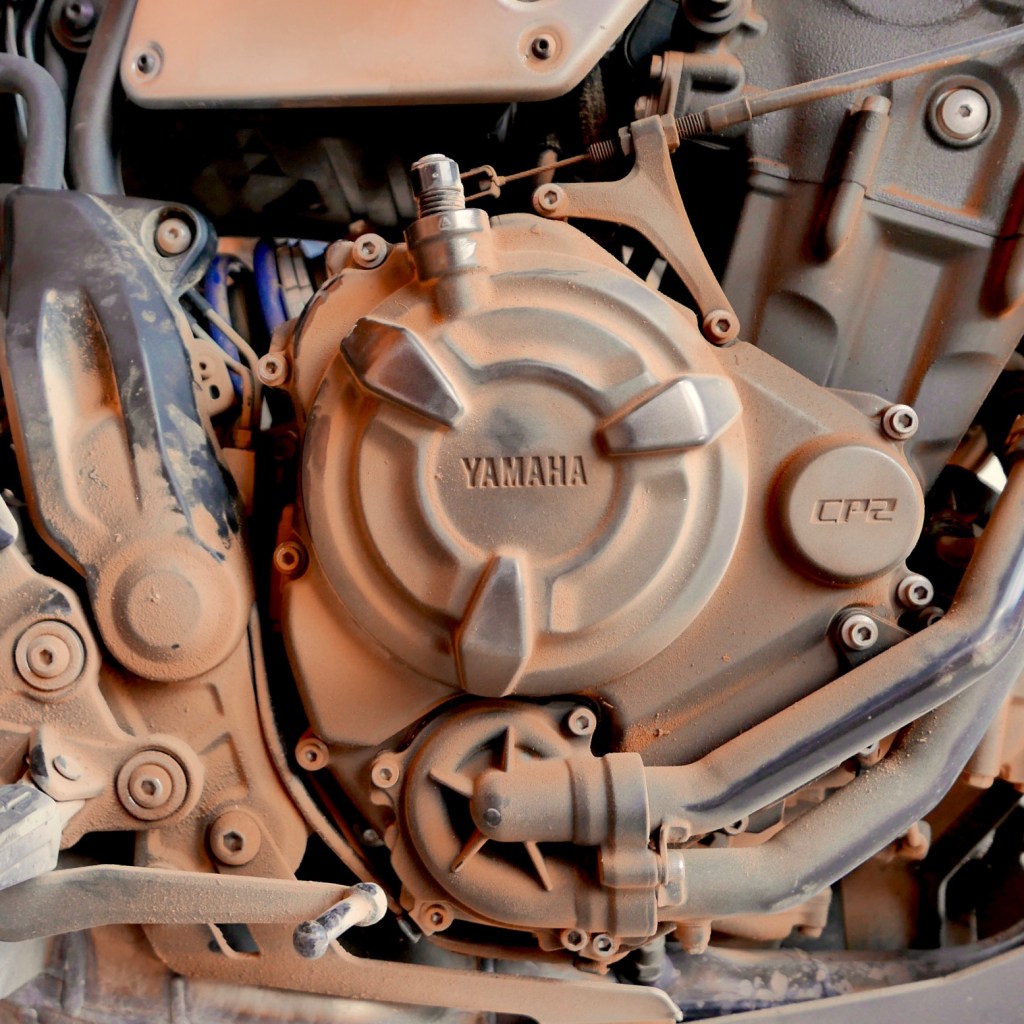

Most are attracted to the better-looking 800 model, but the confusingly named F650GS is actually the same 795cc motor, detuned by 15% to 71hp peaking some 1200rpm down the rev band. Suspension travel is shorter and with a 19in front wheel that makes the seat lower too. Tyres are tubeless and the gearing is said to be from the F800ST road bike, the only flaw on the piste.

At the first service at Vines in Guildford a smaller front sprocket was fitted because swapping cogs was not a roadside job. A bash plate, hand guards and engine bars were also fitted, and Metal Mule supplied a rack, tall screen and radiator guard. With the Tourances replaced with a set of lumpiuer Heidenau K60s and some Enduristan throwovers, I was good to go.

Now we were finally on the piste and so far so good. The track headed south back to the escarpment edge. Far below in the haze lay my destination, the dune-basher’s Mecca of Erg Chebbi, Morocco’s only distinctive sand sea. Just 20 miles long, they come to gaze in wonder at its forms or test themselves on its rosy flanks. I knew that once I dropped off the escarpment within sight of an Algerian border fort and headed towards Chebbi, things would get sandy; that’s rare for Morocco and hard work on 230 kilos of bike.

Sure enough, as the mid-afternoon heat peaked I found myself pushing alongside the GS in first, the tall gear churning the back wheel as the bike inched across the sands. Experimenting with the K60s still at road pressures, this was to be expected, so the slightest forward progress was better than losing momentum. It was only an hour or two’s effort but that was enough to drain me, and as I neared the firm gravel plains alongside the Erg, I unzipped my sweat-drenched jacket and cruised around lazily from one auberge (desert lodge) to another until one took my fancy.

I’ve done enough of these short adventure rides to know that at some point a spanner as long as a pool cue would be thrown through my spokes. That reversal had already come and gone so I felt myself in the clear. On berthing at the Moroccan port of Nador I noticed my tailpack of camping and riding gear was missing. It was one of the ferry crew for sure, but my protests were in vain; they blamed the passengers and I blamed my laissez faire attitude towards security. All that really mattered: GPS, maps, iPad and other valuables I’d kept with me for the six-hour crossing. I was fuming of course, but the mission had not been compromised. I just wouldn’t be camping as I’d hoped, and the bike would be a little lighter.

Black Rock Desert

Encouraged by the low-seated 650 and the K60 tyres, I was ready to tackle a trickier stage I’d spent months preparing for. West of Erg Chebbi, between the N12 highway and the popular M6 route along the Algerian border, close scrutiny of Google Earth revealed a network of possible tracks. Unmarked on most maps and restrained by convoluted topography, many tracks ended at mines that scoured the blackened mountainsides which gave the region its name: sahra aswad sakhar (I made that up). I wanted to cut through the middle to the west, but was unsure how- or if it all linked up. One route looked like it might work out, but somewhere I’d need to cross the desert course of the Oued Rheris river.

A few days earlier I’d passed close to the source of the Rheris up in the High Atlas. A tip from a local auberge owner had led me up a mountain track cut by the legionnaires in the 1930s high above a narrow gorge to evade ambushes by the as yet unpacified Berbers. Up at over 2200m in the sleet (above), the 650’s computer had read just 1ºC; and today down at Erg Chebbi overnight winds had smothered the skies with a desert haze that might bring rain.

Crammed between desert, ocean and mountain, erratic Moroccan weather can throw everything at you during a springtime fortnight. It was going to be an adventure for sure, nosing out a way though the valleys and around the escarpments of the BRD, but hopefully something would come of it.

The great thing about riding in Morocco is that distances are short by the Saharan standards on which I cut my teeth in the 1980s. Few tracks exceed 200 kilometres between fuel or towns so there’s no need for extra tanks or – luckily this time – even camping gear. Follow a likely looking track and it’s bound to lead somewhere. It might be a dusty mine site or a stone clad Berber village, clinging to a canyon side and barely changed since medieval times.

I rode south past Erg Chebbi (above) as the forerunners of the Rallye Aicha des Gazelles tore along the base of the dunes. At the village of Taouz I set off on my own one-man rally, which initially required crossing the flood plain of another big desert river, the Oued Ziz. Three years ago on my Ténéré, the Ziz had been flowing past Erg Chebbi fit for rafting, nixing my chances of getting into the desert noire. This time round I had a few moments as the BMW sank into the chalky mud; getting mired within sight of the village would not be a great start to the day, and I reminded myself to take some air out of the tyres.

On the far side a moped-mounted tout soon zoned in and offered his services but I was determined to work it out myself. As is often the case, tracks can be confusing near a settlement, and after a bit of blundering with my moped mate never far behind (“ooh, you don’t want to go that way, chum…”) I picked up a likely trajectory to the northwest.

The track forked and reconverged around obstacles, a common trait in open deserts that can unnerve the inexperienced. After a few miles it picked up a bigger piste that had been pulverised into a flour-like powder by mine trucks. Even here the K60s kept their composure and I came to a junction where a passage led to an abandoned village I’d spotted on Google Earth. Down in a dry creek below the ruins I marked a waypoint and the depth of a well for the book, and rode on, taking any track that erred west. Stopping frequently to mark each junction, I came to a gap in the range (above) where the main track led north to the Rissani, a fall back destination if things didn’t go to plan. At this point a lesser route swung directly west into the Black Rock.

Cry me a river

The fast track soon swung off to the south, probably a service route for the village of Remlia on route M6. Heading there was another contingency should I get stuck, because I knew that up ahead the state of the Rheris would make or break my day. I lit off westwards cross-country and after a few miles picked up another track.

The valley narrowed and I squeezed through a sandy passage that in turn led to a basin, a kind of inland delta or reservoir filled when the Rheris was in flood. Soon I was jostling the GS over the salt-capped mounds of crusted mud, and with a fright, felt the GS sink and slow to the mud below. I dashed directly for the edge of the basin where firmer tracks skirted the hillside.

The baked rim of the muddy delta led over a rocky pass to a field of small dunes where the track ended abruptly on a flood-carved riverbank (above). Down below a ribbon of water separated me from the far side and another field of small dunes which stretched on who knew how far. I turned the running GS into the wind to cool off, hung my heavy jacket and lid on the bars and slithered down the sandy bank to the water’s edge. One thing was for sure, once l rode down that sandy bank there was no getting back up. This was a one-way trip to whatever lay beyond. At the river the water was only ankle high and the bed was firm; I could ride through this. But up ahead a long sandy ramp rose away from the channel and would sap the 650’s traction. I walked up and decided that it too was doable, then waded back to the bike, dropped a couple more pounds from the Heidenaus and paddled down the bank and through the water.

On the far side I paddled the GS hard up the sandy ramp with the engine pinking, tyre spinning and the fan whirring fit for takeoff. I kept at it until the terrain relented and I was out of the dunes. Up ahead a well caught my eye, the first I’d seen since the morning. I pulled up for a breather and kneeled by the camel trough for a cooling splash and a snack. An hour or so later a final expanse of sand led me out of the Black Rock’s escarpments and onto a sandy plain.

I ignored what tracks there were and instead rolled west cross-country towards a distinctive peak where I was sure a haul road led back north to the N12 highway. At one point a local guy joined me on his 125 and we diced in the dirt until he spun off on some unknown shortcut.

I’d taken a chance and my mini-adventure had panned out. I’d found a way through the Black Rock. It’s commonly said that the era of grand exploration is long past. That may be so, but the thrill of taking on the unknown, be it a transcontinental ride or just a day in the desert, is why they call it adventure motorcycling.