Africa Twin Index Page

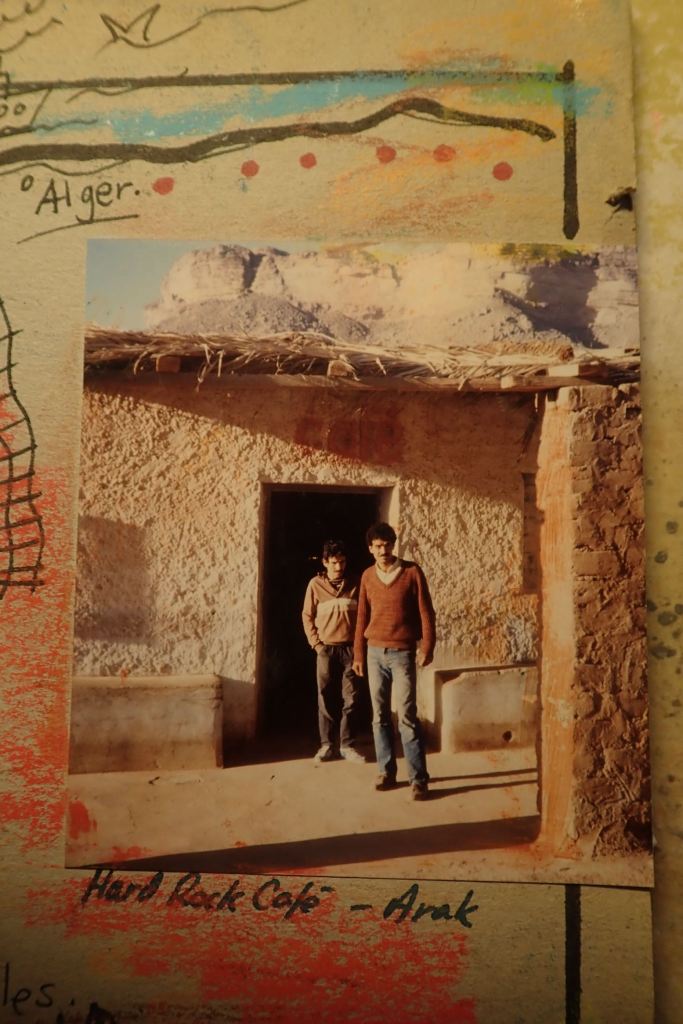

‘Hotel Sahara’

Africa Twin in Morocco 1

Africa Twin in Morocco 2

Morocco Overland

After hurriedly leaving my damaged AT in Morocco back in March 2020, in October 2021 I finally managed to fly down, fix it up and go for a little ride, before flying back home. The plan was then to fly back in early November, do a tour with a group, then ride the Honda back home before it got too wintery.

With the current twist in the Covid shitshow it’s hard to keep track, but mid-October 2021 the UK was doing badly in the pestilence league. Hold your nerve they said; it’s a cunning plan to get the UK’s spike in early to avoid a big winter spike when there would be a spike anyway. Well, we’re getting a big spike alright – today it’s getting on for three times the October number, though hopefully without the drastic consequences of last winter.

Nevertheless, in response to the UK’s October numbers, Morocco suspended all UK flights so my tour had to be cancelled. Flying in via Spain or France was not a foolproof dodge: people tried that last year and got caught. Plus now, every extra country adds Covid paperwork complications. In the meantime, I still had to get my AT out of Morocco before the end of 2021, otherwise the Customs would turn the bike into a pumpkin.

By early November I’d heard of a Brit flying to Morocco via Portugal with no problems (which of course makes you question the point of the flight ban). So the Mrs and I got our heads round French Covid regs, took a train down to Marseille and rented a cabin in the hills for a few days – a pleasant Provençal interlude. It was great to be back in southern France.

Meanwhile, an old mate was passing out of the Med on the way to the Canaries and beyond in his refurbished catamaran which he’d picked up cheap.

‘Andy, pick me and the bike up off a Moroccan beach and drop us in Spain. We can do it in a day.’

‘No can do señor. Private boats are banned from mooring in Moroccan waters at the moment. We could do it in Mauritania?’

Mauritania? Who’d want to go there? Oh, me about 20 months ago. But from Morocco that border was still closed.

While in France I needed to track down a PCR lab to obtain a <48-hour negative result before flying from Marseille to Marrakech. One break in this paperwork chain and the whole plan crumbles. It’s only money and rebookings and inconvenience of course, but it’s still frustrating and stressful. One day we’ll all get used to these post-Covid measures, but like Carnets or visas for West Africa, it’s one hurdle after another and can take over the trip.

That night my resultat: négatif pinged on the mobile and by the next afternoon the Mrs was on a Paris-bound TGV and I was settling into my usual Marrakech hotel.

It was Tuesday. My ferry was on Saturday at 5pm – just a day’s drive to the north before a 40-hour marathon to Sete, in France. [There have been no ferries to Spain since Covid broke in March 2020.]

But first I had to track down a Customs office in Marrakech and get my long expired TVIP renewed. I could easily imagine the scenario:

‘Oh no no no. We can’t do this here, you fool!

You have to go to Casablanca to request a pre-appointment voucher application form. But they’re closed till next week.’

I found the place not far away in a side street with the familiar blue and grey livery of the Bureau des Douanes.

I walk in, he pulls his mask up. So do I. It’s the law.

‘New TVIP?’

‘Wait there.’

A minute passes.

‘You can go in now.’

Another sixty seconds later I walk out with a printed-off renewal notice set to expire December 31, 2021. Result!

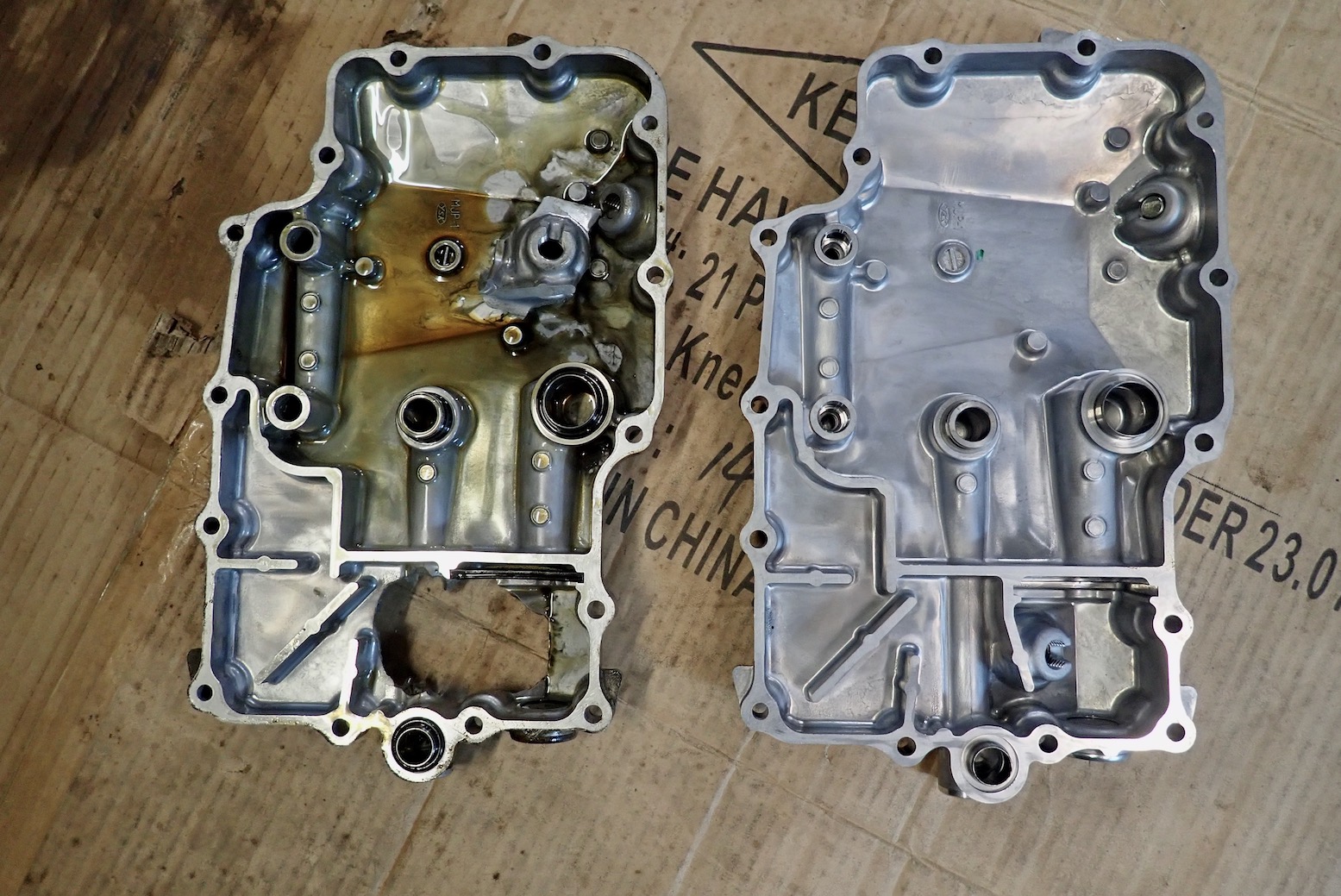

I walked over to Loc Rentals and we talk about the whole darn situation, bikes and what not. They tell me their 850-GSs have been surprisingly unreliable t th point of getting ditched, while the 750GS version I rode a couple of years ago has been fine. In the last two weeks a bunch of my spring 2022 tours have filled up. I keep a fairly low profile so never know quite how this happens, but people are clearly gagging to get away on a mini adventure.

Still caked in Western Saharan dust, my Africa Twin is perched on the ramp down in the basement workshop, poised like Thunderbird 2, ready for lift-off.

Meanwhile, I’d got it into my head that I needed another PCR test to be allowed on the ferry. That was the case on leaving Morocco a few months ago; a UK stipulation. I find a walk-in lab nearby, but asking around online and reading between the lines on the Italian GNV ferry website, it seems my Covid vax proof should be enough for France (but not for Italy), as present regs stand..

I decide to leave Marrakech on Friday and return to the Hotel Sahara in Asilah. That gave me some elbow room for cock-ups and left just an hour’s ride to the port next morning.

Good decision, it turned out.

But not good enough.

At this point I was checking the HUBB Morocco forum regularly. Thursday evening someone posted that all planes and boats to France would be suspended from tomorrow night, 23.59.

Bugger!

This wasn’t a total border shutdown (that would happen three days later), just France following in line with the UK rule, so all was not lost. The Italian GNV ferry also served Barcelona and Genoa, so there was a hope it would simply re-route to either port, about the same distance to the UK, give or take a couple of mountain ranges. GNV’s website and twitter said nothing new, and a helpline woman said ‘see the website’.

It left the question: do I ride the 600km to TanMed port tomorrow only to be told next day’s boat was off? That would mean riding back to Marrakech, re-stashing the bike at Loc and joining the scrum at Marrakech airport to grab a flight to anywhere that was still on the list, and from there find a way on to the UK.

Leaving the bike with its expiring TVIP was the least of my problems. The Moroccans had extended it before; they’d probably do it again (in December 2021 they did, for another 6 months).

‘Last boat out of Saigon’

I woke up Friday morning to some good news. The Moroccans had relented and extended the deadline till Sunday! Saturday’s ferry would be the ‘last boat out of Saigon’ for a while, much like my last flight back in March 2020.

So by noon I was barrelling up the deserted A3 autoroute north of Marrakech with an easy 500 clicks to Asilah.

As I neared the coast I tracked the path of showers running up from the southwest, hoping we’d not converge. My heavy canvas Carhartt coat wasn’t really made for that, more for Montana blizzards. I slipped behind most of them but caught one short downpour. In the 120-kph breeze I dried off soon enough.

By late afternoon I’m back at the Hotel Sahara where this sorry saga began some 6000kms and 600 days ago. I’m the only one staying but at only 9 quid and far from a dump, this must be one of the best deals around.

Assuming I get on the boat tomorrow, there were still a number of hurdles to jump, not least a 1000-km ride across France. I didn’t want to check the weather – que sera, sera. Either it’ll be tolerable with the gear I gave or it won’t be.

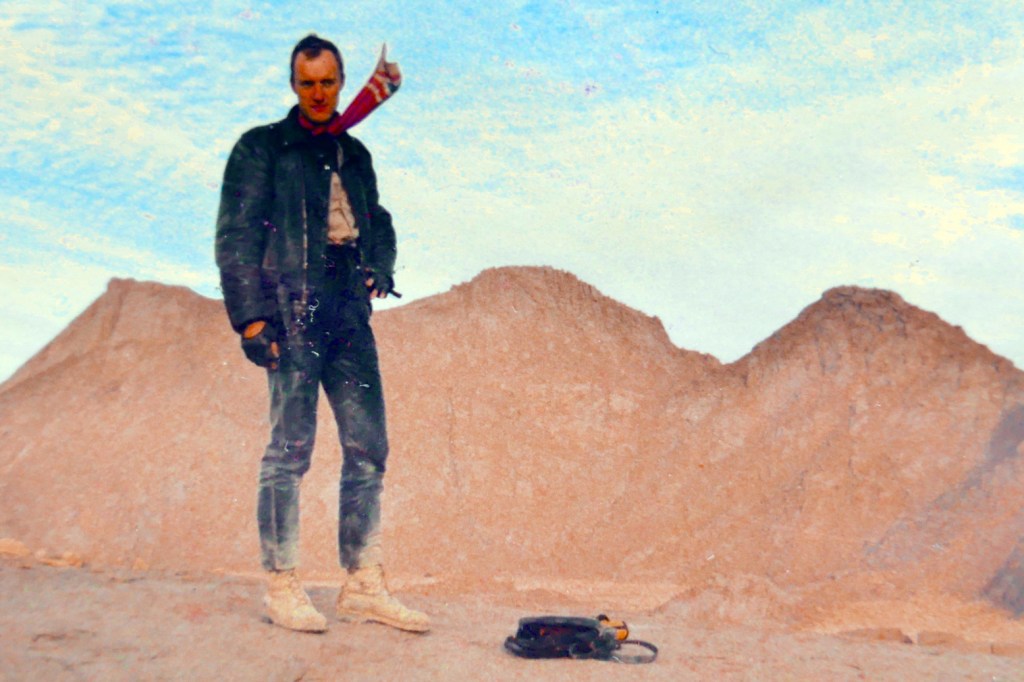

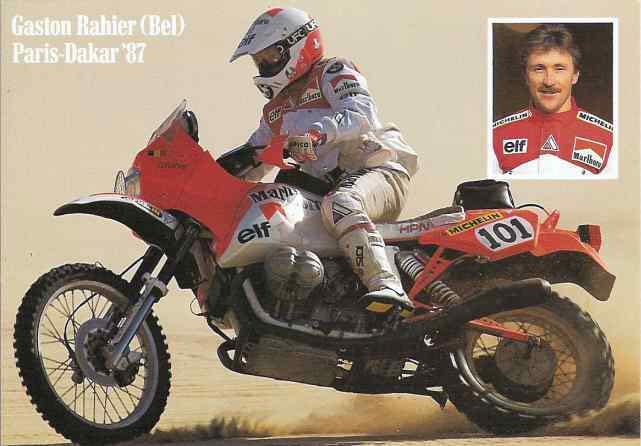

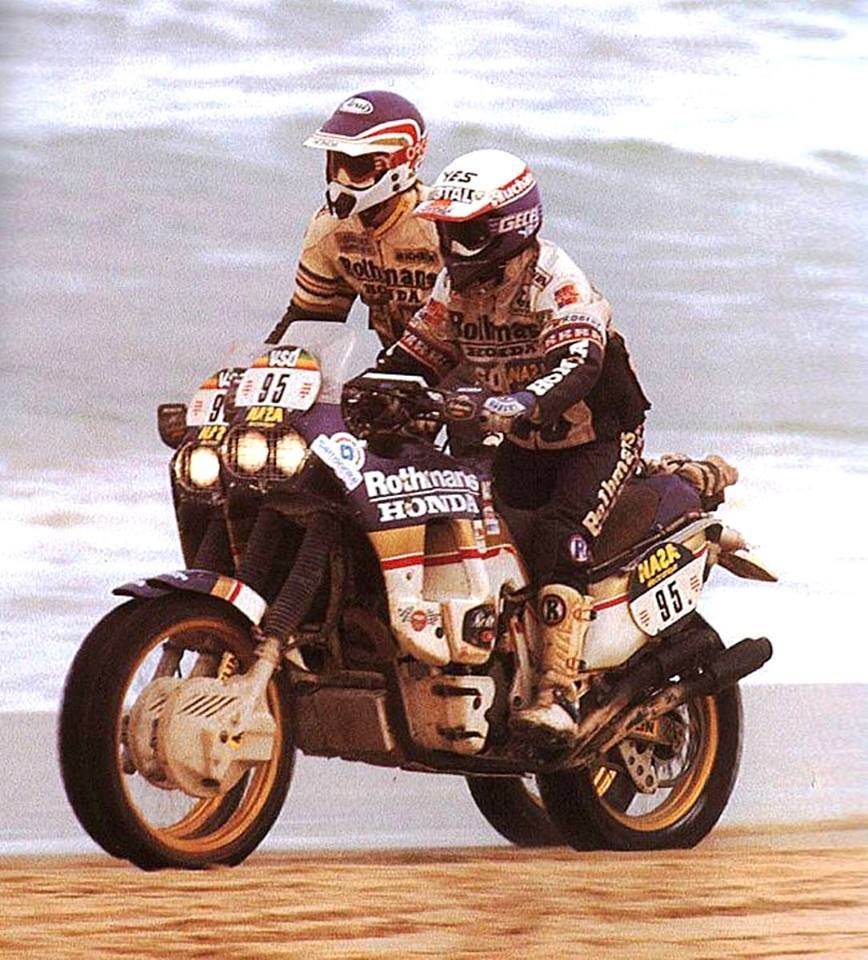

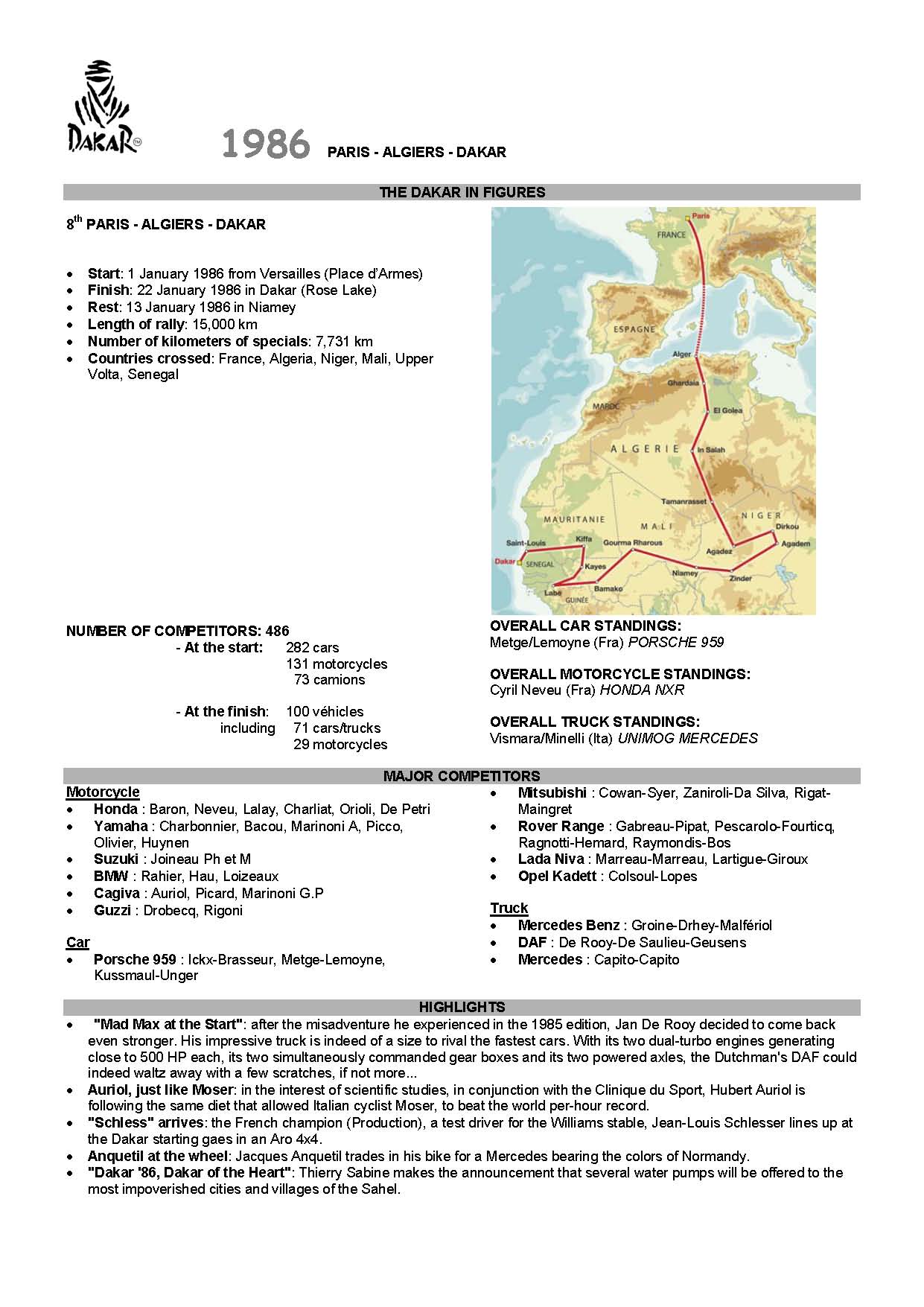

I used to do that winter ride a lot in the 1980s, Marseille-bound for Algeria. Only now I have the combined miracles of a Powerlet heated jacket, a windshield and a protective film of late middle-aged blubber. Plus a meaty CRF1000L that can punch through the windchill at 120kph with one leg in the air.

It was just an hour to the port so I took it easy Saturday morning until a text from GNV ferries pinged while I was having breakfast at the Cafe Sahara.

Attention all passengers

• Make sure you turn up with ALL PCR/Vaccination documentation or you will not be allowed aboard

• Check-in closes promptly at midday

Shite, I’d better get a move on. The mention of PCR set the nerves a-jangling again until I realised the forward slash meant ‘PCR or…’ not ‘PCR and…’.

I stuffed in my croissant, knocked back my coffee, and then had the usual dance to get someone to wake up and let my AT out of the garage.

I rolled off the autoroute and into Tangier Mediterranean (‘TanMed’) port an hour later. This is a huge, Alcatraz-like facility 50kms east of Tangiers city, where labyrinthine causeways and ramps lead down to the quays. Sub-Saharan migrants who periodically assail the barbed fences of nearby Ceuta don’t waste their time here; it’ll end up with a stiff beating from the cops who patrol the 20-foot fence.

In the port, the first hurdle is to turn an internet-printed ‘ticket’ into fungible ‘GTF Out of Jail’ vouchers at the GNV counter. But first, you need to get past matey who’s taking photos of PCR/Vaccination papers. Except he’s wandered off for a fag. In the meantime at the GNV counter, a Remonstrating Man is having it out with the unfortunate behind the glass.

‘But I bought this ticket off ferryticketscam.com!’

‘Sorry sir, you’re ticket is not valid. Please move along. Next!’

Remo Man won’t budge; security are called and he moves aside to remonstrate with them instead.

‘Look, I bought it off ferryticketscam.com! It cost me 550 euros!’

‘Sorry sir…. we literally could not give an actual toss.’

In the meantime, the stalled queue is getting antsy, including me. It’s not helped by people joining the line from both ends or squeezing in with a nod and a wink. Half an hour later I’m there and snatch my handful of tickets and vouchers. I ride on to the Police for an exit stamp. He puts my passport into a reader, then mentions I need to get some piece of paper from Customs. Yea, yea.

Customs is a bit slow as my new TVIP print-out needs approval from the boss, but with that done, I slip past the long queue to the giant x-ray machine: a huge metal frame on rails and with cables as thick as your arm, that’s pushed back and forth by a lorry with a bank of screens inside.

On a bike, I’m invited to the front. Protocol-wise, it’s exceedingly un-English but no one minds at all.

Try it at home and ‘Oi, biker – wot you effing playing at?!’

This is why we like bike-friendly continental living.

We’re told to step away from our vehicles to limit radiation. Are they looking for explosives, stowaways, or just hashish which is cultivated openly on the slopes of the Rif mountains a 100kms south of here? Who knows, but next up an Alsatian gives us all a darn good sniffing. Moroccan wheeler-dealers in beaten-up vans full of whatever sells in Europe unload every last box and bag with resignation. Foreign tourists, and especially bikers, are hardly ever searched.

That all took two hours but I’ve reached the next level. I’ve taken my redpill and am ready for Extraction so I ride down to the queue assembled in front of the huge brick of a ferry.

I eye up other overlandy vehicles: a tasty 4×4 Pinzgauer from the 1970s or 80s done up in Tibetan prayer flags, and a huge quarter-million euro M.A.N camper that’s probably better inside than our London flat.

Another two hours pass then barriers get shifted and engines fire up. I’m invited to the front again and prepare to part with Moroccan soil and ride up the Ramp of Salvation to reach the final level of the Ferry Matrix Game.

But first another passport and ticket check, just in case I parachuted into the port with no one noticing.

‘Where is the passport exit stamp?’

‘I dunno, it’s there somewhere. Let’s have a look.’

It’s hard to read one faint, overlapping stamp from another. I’ve amassed loads over the years. Tuesday’s airport entry is there alright, but I can’t see today’s exit stamp.

He takes it up the chain of command and various cops get on their radios.

Bloke in hat: ‘Where is the police exit stamp?’

‘I dunno. Just give me a scribble and let me on anyway.’

They jabber into their radios and phones.

‘My friend. You must ride back and get the stamp. Don’t worry, it will take 5 minutes.’

FF’s Sake! I can’t face slipping back into Liquefaction. Hours ago immigration cop in his booth had one job: take passport, check computer database, stamp it and hand back.

OK, I suppose that’s four jobs, not including breathing, blinking and rearranging his bollocks.

I ride back, go the wrong way, get stopped, explain myself, radio calls, squeeze through barriers, get sent back, go the other way, ask a cop, he shrugs. Ask another.

‘Why did you not get the exit stamp?’

‘I don’t know, do I!? I handed him my passport, he did his thing and gave it back.

How could I proceed without it?’

This will the Last Ferry for months so I’m careful to lay on just enough indignation without becoming another Remonstrating Man. They take my passport. It checks out on the computer. I get stamped but make sure to see exactly what page it’s on. Then I bomb back, jumping the queues at the Customs, the x-ray machine, and the sniffer dogs, expecting whistles to blow and sirens to sound.

Back at the ramp I’m allowed to ride aboard, park by the few other bikes and load the tail bag up with all the mission-critical things I can’t afford to get pilfered. The Italian and Filipino crew direct me to my cabin where I spread out enough boarding cards to start a small casino.

Jesus, Mary and Joseph on a wee donkey, does it have to be this hard?

The 5pm departure comes and goes and the sun sets over the Atlantic but there are no promising throbs from the engine room. I’ve been on enough long, overnight Med ferries to know they never, ever leave on time.

7pm and down on the loading ramp another Man surrounded by hi-viz crew, indifferent cops and insistent GNV admin is Remonstrating like his life depends on it. Arms gesticulate aggressively. Voices are raised. Some shoving occurs.

He’s as mad as hell, and he’s not gonna take this anymore.

9pm. Another 100 cars and vans show up ride up the ramp. Maybe GNV is making the most of last-minute ticket sales. Who knows when this service will start running again. By tomorrow night all Moroccan borders will shut in response to the growing Omicron threat.

At 10pm, ten hours after check-in closed and five hours late, there’s a rumble and a judder from far below. The M/N Excellent pulls back from the bumpers and glides in between the breakwaters. This is the same confidentiality named Excellent that came in a bit hot at Barcelona port a couple of years back. Some muppet forgot the ABS was switched off after a spot of off-roading.

For me the immense feeling of relief when a ferry leaves a North African port has become embedded deep in my brain’s maritime lobe. After so many North African scrapes over the decades, not least this one, you feel like yelling back at the shore

‘Come and get me now, you bastards!

(And no, I don’t care if this boat rams into a Balearic island and sinks, but thanks for asking).’

Meanwhile, aboard the Excellent every 30 minutes the tannoy chimes up in three languages to tell you to wear a mask, it’s the law. Most Moroccans ignore this instruction, maybe because Morocco never got hit as hard as northern Italy did last year. Or maybe they have no reason to trust authority.

As long as you score a cabin to yourself, I love these long ferry crossings; when they’re not ramming quays, these modern ships ride the seas like a K1600 GTL with the platinum ESA package. ///delighted.ferrying.northbound

Part 4 shortly